PLACES OF DARKNESS

AFRICA'S MOUNTAIN GORILLAS and THE WAR IN CONGO

(published in National Geographic Adventure;

Anthologized in The Best American Travel Writing 2004;

Winner of the 2004 PEN Award in Journalism and a Lowell Thomas Gold Award)

I. Rutshuru, Eastern Congo

“How are your gorillas?” Colonel Bonane asks. The leader of the RCD (Congolese Rally for Democracy) rebel forces terrorizing eastern Congo, he steps out of a night so complete and starless that it is as if the darkness itself has produced him. Well over six feet tall, wearing camouflage fatigues with a green beret folded neatly under an epaulette, he has the powerful, arresting physique of a warrior. All of us—including the park warden, a Congolese mountain gorilla conservationist named Vital who acting as my interpreter, and an RCD official sent to monitor me—stumble out of our plastic chairs, give deferential bows, smile lavishly and painstakingly. We need the Colonel to like us. This man can, with a word, save or destroy us.

Bonane is pleased by our display, entreats us to sit down, make ourselves comfortable. “And you,” he demands in French of me. “Why are you here?” There is instant silence around the table; his officers level sharp, steady stares at me.

Vital jumps in, explaining that I’m a writer come to Congo, to their war, in order to see the mountain gorillas. Or, at least, what’s left of them. I don’t reveal my own, deeper interest: that I’d like to know what motivates people, such as the late Dian Fossey, to save these animals in an area of the world that seems hell-bent on its own destruction.

“Ah, the gorillas!” Bonane laughs. His laugh is deep, resolute, like the crack of a whip. We all come to attention at its sound, wait for whatever is expected of us. “The gorillas!” Bonane exclaims. “I love the gorillas!” He grins and sits back in his chair. His men squeal in laughter: it is a joke. All of the men with me, many of whom have devoted their lives to saving the rare gorillas, who work for the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund (DFGF) Europe, laugh along with him. You do not want to piss off the colonel.

Overhead, a single fluorescent bulb hums and spits out light, large moths diving into it like kamikazes. The RCD soldiers eye me, their AK-47s leaning daintily against their chairs like parasols. I stare back at them, match their filmy gazes with my own. I don’t know what’s a more incongruous sight in this seedy restaurant in this war-exhausted town: a writer interested in something as novel as the gorillas, or a woman. The women in these parts are noticeably absent after dark; they hide themselves to avoid being gang-raped by drunken RCD soldiers. Rape could accurately be called eastern Congo’s favorite national pastime. I know that only the official presence of the town mayor (a high-ranking RCD crony) and the RCD government monitor keeps me in a safe, hands-off status. My two protectors are starting into yet another large bottle of Primus beer, slurring their words and stroking their crotches, sharing mzungu (white person) jokes with some of the soldiers nearby. I look into the darkness to the south, where the gorillas are. I wonder if they are hiding, cringing in the shadows of their jungle home. I know I would be.

It is hard to talk about the mountain gorillas and not talk about the chaos surrounding them. Perhaps more than any other animal on earth, these creatures’ fate is inexorably tied to war. There are only about 650 of them left. Fewer than half are in Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable National Park bordering Congo; the others reside farther south in the Virunga Mountains, on a mere 166 square miles of protected land where Rwanda, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire) meet. Both populations live in the epicenter of one of the world’s most violent and unstable regions, a place rife with corruption and greed, with unchecked exploitation of natural resources and an unfathomable disregard for human life. It was in 1994 that the world got its first enduring taste of this region with the Rwandan genocide. The conflict spilled into neighboring countries as the Hutu militias, known collectively as the Interwahamwe—whose war with the minority Tutsi tribe left about 800,000 dead in 100 days—fled into the jungles of eastern Congo to regroup and launch further cross-border assaults. Rwanda and Uganda sent their armies in after them in 1996, ushering in the Congolese civil war. It is a conflict that quickly drew in the armies of Zimbabwe, Angola, Namibia, and other countries, and has created an unending nightmare for the U.N. Only educated guesses about the number of dead can be made in a region that hasn’t had an official census since 1984, but it is estimated that the war has claimed as many as 4.7 million people—the worst loss of life in an armed conflict since World War II.

And the war shows no sign of stopping. Local tribes, assorted militia groups, and clandestine army factions from neighboring countries have found the fighting lucrative beyond all expectation. In a country like Congo, where the average person can expect to make no more than $120 a year, fortunes are made hourly by whoever controls mineral-rich areas. More profitable than gold or diamonds, and more easy to extract, is the rare substance, colombo tantalite, known as coltan, an essential ingredient for microchips and cell phones. Found almost exclusively in eastern Congo, it can bring in a whopping $400 per kilo in the international market, giving rebel factions and neighboring governments a financial reason to keep the war going indefinitely. Only when the Congolese conflict caused a temporary suspension of coltan mining did the western world feel the reverberations of a war it had all but forgotten: Sony was forced to delay the launch of its popular Play Station 2.

As for the mountain gorillas, the animals have so far been blessed: the mineral hasn’t yet been found in their habitat. Where it has been found—most notably in the eastern Congolese park, Kayuzi-Biega—the population of eastern lowland gorillas has been decimated by 90% and the park’s jungle elephants, once numbered at 350, are down to two. With so much wealth being pulled out of the ground, no one, neither human nor animal, is safe anymore. “We fear for the mountain gorillas in the Congo,” says Fortunate Muyambi, project coordinator for the Mountain Gorilla Conservation Fund (MGCF) in Uganda. “Once the gorillas cross into unprotected [Congolese] areas, we don’t know what will happen to them. If there’s a prolonged war, there will be extinction in a very short time.”

The main reason for the animals’ continued survival is due to the tourist revenue they bring in to the area. Quite simply, they have been worth more alive than dead. In Rwanda, gorilla tourism accounts for the third largest source of revenue for the country; in Uganda, the fourth. Congo has seven habituated groups—such groups are specially trained to accept the close proximity of humans—the largest number of the three countries. Back when it was still Zaire, the country had a thriving, lucrative tourist industry that included upscale lodges, gorilla safaris, and jungle treks. Now, with the lodges destroyed, the hiking trails frequented by the genocidal Interwahamwe, and tourists banned altogether, Congo has lost all of its revenue from the gorillas—and thus the incentive to protect them. Though there is a national park ministry, in eastern Congo it’s run by RCD-appointed bureaucrats whose commitment to the protection of animals is questionable at best. Vital, a straight-talking ecologist who recently won a conservation award from the BBC, explained it to me bluntly: “It’s a crony government. These people don’t have any interest in conservation. The first purpose of RCD officials is achieving economic gain.” The RCD does not want its exploitation of the parks publicized or interrupted—hence the man sent monitor my every interview, to keep me always within his sight. I am not supposed to let my focus waver from the gorillas.

Before I came to Africa, I spoke with a representative of Doctors without Borders who criticized the way people give more attention to the plight of the mountain gorilla than they do to the tragedy of the human beings. It seemed a valid and important concern for which I did not have a ready answer. Can the gorillas’ story of survival be seen as a classic parable of hope? Of grace rising like the spring of new leaves from a landscape devastated by war? But the thought is grossly romantic, makes me shake my head before Bonane and his men. Grace. Here? I know this: a staggering 82 Congolese park rangers have been killed since the war started, making mountain gorilla conservation one of the most dangerous professions on earth. Yet the people who have devoted everything to work with these animals tell me that there is something ineffable about them. One Rwandan park ranger, named Jean-Bosco Bizumuremyi, who endured an Interwahamwe attack to return to his gorillas—he showed me a machete scar across the top of his head—said: “Unlike us, the gorillas do not try to kill each other.”

Colonel Bonane sees me writing in my notebook, and he waves angrily at me, issues an immediate decree. An apologetic Vital whispers in fervent English: “Stop! Don’t write anymore! Close that book.”

I close it.

Bonane sighs and waxes nostalgic: “Ah, the gorillas…”

*

Later in the evening, in the dank cement cell of a room where I’m spending the night in

Rutshuru, chair propped against the door, my knife out on the table beside me and opened to the largest blade, I reread Dian Fossey’s Gorillas in the Mist. Fossey was the first person to launch a crusade to save the gorillas under the tutelage of the famous paleontologist Louis Leakey, back in 1966. With very limited funds, she went alone into the Congolese Virungas to set up a base camp to study what was then a dwindling population of only 240 animals. Even then, she observed that “one of the greatest drawbacks of the Virungas is that it is shared by three countries, each of which has problems far more urgent than the protection of wild animals.” After barely a year in her new home, she was forced to flee when war broke out. She soon returned to the Rwandan Virungas, to set up the now world famous Karisoke Research Center. To pay for increased patrols in the Virungas, she established the Digit Fund, named after her favorite silverback, who had been killed by poachers.

I met Fossey’s successor Ruth Keesling in the lobby of the posh Hotel des Milles Collines in Rwanda’s capital, Kigali. Shortly after Fossey’s death in 1985 (two assailants, believed to be local poachers, killed Fossey with a machete blow to the head), Keesling took over the Digit Fund, changing the name to the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund Europe. These days, she runs the Mountain Gorilla Conservation Fund. Flashing bright blue eyes and an impish grin, the 73-year-old Keesling greeted me with the unwavering energy you’d expect to find in a woman half her age. For the past 19 years, the American has made frequent pilgrimages to Rwanda and Uganda in order to meet with the leaders of both countries and negotiate on the gorillas’ behalf. If in-your-face coercion was Dian Fossey’s specialty, Keesling’s secret weapon is congeniality. Having experienced firsthand the rare influence she had over people, I could think only this: Here is someone who can get anything she wants. Which has been good news for the gorillas. Though few outside of animal conservation know her by name, her efforts have been one of the

main reasons why the gorillas have survived into the 21st century.

Most notably, she hasn’t let central Africa’s unrest stop her. “I don’t worry about things like that,” she told me over her customary double-shot of Chevas before dinner, waving the instability aside like so much minutiae. She recalled arriving in Kigali the day the genocide ended and the Tutsis liberated the city from the Hutu Interwahamwe—there were bodies rotting on the streets, buildings pocked with bullet holes, corpses filling the basement of her beloved Hotel des Milles Collines.

“I just didn’t think a thing about it,” she said of her decision to fly in under such circumstances. “We came here all the time.”

Keesling explains her commitment by saying that she likes “solving problems,” but her love for the animals is undeniably profound. She knows most of them by name, refers to one favorite silverback, Shinda, as her “boyfriend.” Her tale of how she first met Fossey in 1984 is a favorite of hers, told so many times that it had the rote ring of legend: “I met Dian at a dumpy hotel in Rwanda. She was dynamic, in control. I was so impressed by her mission. And Dian said to me, ‘Ruth, there are only 248 mountain gorillas left in the world. They’re all going to die and I’m going to die with them.’” Keesling brought Karisoke its first veterinarian in 1986, and in later years raised enough funding to see poaching almost completely eradicated from much of the gorillas’ habitat.

After our introduction in Kigali, Keesling and I went to visit Fossey’s grave and the remnants of the original Karisoke Research Station, all located above 10,000 feet in Volcanoes National Park in the Rwandan Virungas. On the way up, we passed large tracts of farmland—all well within the official park boundaries—that had been cut from virgin rainforest. In the years after the Rwandan genocide of 1994, international pressure called for the repatriation of thousands of refugees who had fled to camps in Congo. Only when civil war erupted in Congo did many of the refugees return, some resettling on the only uninhabited land they could find: around the fringes of Volcanoes National Park. The result is complete deforestation of the park’s mountains as far as the cloud line.

We trudged up the muddy path, reaching moist montane forest filled with giant hagenia trees draped in a kind of Spanish moss. The snow-covered 14,000-foot peaks of the volcanoes lorded over the countryside, revealing themselves through breaks in the clouds. I half expected some gorillas to come loping towards me from out of the brush. Instead, from some far away point in the jungle, a male gorilla thumped his chest and let out a deep bass tremolo that echoed across the mountains.

The animals’ extreme alpine habitat has been their only real defense against humans. They weren’t known to European explorers until 1902, when Oscar von Beringe, a Belgian, shot the first one he discovered. In the 1920s, whites decided that the rare gorillas ought to be kept alive rather than killed, and so the Belgian government, then Rwanda’s colonial ruler, formed Africa’s first game park, Albert National Park, in the Virungas. By not overlapping with the habitat of other large primates, the mountain gorillas have naturally quarantined themselves from such diseases as ebola, which is currently decimating the chimpanzees of Uganda, and they have so far avoided being caught in the bush-meat trade that has ravaged populations of the less glamorous lowland gorilla all across central Africa.

Still, their status as a highly endangered species hurts them in unexpected ways: wealthy outsiders with their own private menageries have offered poachers upwards of $25,000 for the capture of a single baby, which entails killing several of the adults protecting it. There were two attempts in 2002 to steal babies—one in Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, the other in Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park—which resulted in the capture of two babies and the deaths of six adults; luckily, one of the babies was recovered and successfully assimilated into another gorilla group. Yet there are concerns that the lawlessness and instability on the Congolese side of the Virungas will make it easier to steal babies from this vulnerable population. “In the spring of this year, we saw a general increase in the wildlife trade in this area from Congo,” said Gil Grosvenor, a board member of DFGF International, “and the [seizing of gorilla babies] suggests that there is now a focused attack on the mountain gorillas.” It is a concern not to be taken lightly; Claude Sikubwabo, Congolese coordinator for the World Conservation Union, showed me photographs he obtained of RCD rebel soldiers engaged in the illegal trafficking of primates.

We finally reached the meadow of Karisimbi, which Fossey describes in her diary as “the most fantastically gorgeous country I never dreamed existed.” It was, indeed, an enchanting place, ancient hagenia trees rising like wizened sentinels to stand vigil over the site of Fossey’s lifework and grave. Appropriately, she was buried in her gorilla cemetery, a martyr for the very animals that had consumed her life. I read the bronze plaque on the headstone—a gift that Keesling had made in Fossey’s memory. Around us, workers for the Rwandan government were busy replacing Fossey’s gorilla grave markers, adding fences and footpaths, and covering the grave with a neat patio of lava rock: upgrades for the tourists. Fossey and her mountain gorillas were about to go commercial, the Rwandan government charging $50 per person for permission to visit the grave.

Of Karisoke, itself, little remained—just some cement foundations and rotting wooden frames. The jungle had already started to reclaim the site, beautifying its recent unsavory history with a cover of new greenery. After the Rwandan conflict erupted in 1993, the genocidal Interwahamwe militias repeatedly pillaged Karisoke, finally using it as a base camp for launching raids against Rwanda from 1997 to 1999. Miraculously, Karisoke’s rangers continued to monitor the gorillas on the Rwandan side during most of the hostilities, and only three animals killed; in Congo, however, as many as17 had been lost.

Given the continued threat of poachers and Hutu rebel encroachment, Rwanda appointed an entire battalion to protect the animals and the tourists who visit them. I met the leader of Battalion 69, Major Kirenga, who said that the Interwahamwe has not been in the park since 2001. “I don’t think they will come back to this area,” he said, “because when they were here in 2001, they suffered.” François Bigirimana, warden of Rwanda’s Volcano National Park, was less sanguine: “Now the situation is OK, but for only a short time. It’s still a big problem for Rwanda. The Interwahamwe keeps coming back.”

Few in gorilla conservation can forget the widely publicized 1999 incident in the Uganda’s Impenetrable National Park, home to more than 300 mountain gorillas, a spectacular area of dense jungle-covered peaks that the locals have long called the Place of Darkness. The name took on a more sinister, ominous meaning as the Interwahamwe crossed into the region from Congo and attacked a tourist camp, murdered a warden, and led 16 foreigners on a death march into the jungle. Eight were hacked to death. To the local people, used to such atrocities, it was business as usual—but it was the first time in years that Westerner civilians had been direct victims of the region’s horrors. The massacre took a devastating toll on Uganda’s tourism industry. Today, tourism has rebounded to be the country’s second largest revenue source. Bwindi now boasts a 76-person strong ranger force with paramilitary training. Still, just a couple of miles from Bwindi’s park headquarters, over some nearby hills, sits Congo.

II. Jombe, Eastern Congo

I see about renting a few RCD soldiers to “protect” me on my journey to visit the mountain gorillas. Assorted militia groups, bandits, and warlords have been staging frequent ambushes on passing cars. The latest ambush on this road, I am told, was just last evening—we had been fortunate to miss our turn.

The last time Ruth Keesling visited this place, in 1998, she, her adult son, a woman from Ohio’s Columbus Zoo, and a couple of local veterinary students were captured by Interwahamwe child soldiers and marched into the jungle to be killed. Ruth recalled it in her typically deadpan way: “I thought, okay, we’re going to get it—I might as well die with the gorillas.” The soldiers held AK-47s to everyone’s head and accused Keesling’s group of spying for the Rwanda’s Tutsi government. Everything looked hopeless, but luck intervened: they had been giving a ride to a former official of the Zairian government, who used his influence to persuade the soldiers to set the captives free. Keesling has not tried to see the Congolese mountain gorillas since.

I have no difficulty finding RCD soldiers willing to be volunteer protectors—all you have to do is offer them enough U.S. dollars and promises of free beer. Vital chooses three individuals who don’t appear to be drunk or drugged up yet, and our large group, including an additional three armed Virunga National Park rangers, presses into the ancient Toyota minivan I’ve rented. We head into the countryside, past overgrown fields and mud-and-wattle huts. “There are two types of ambushes here in Kivu Province,” Vital tells me. “The first is the ‘political ambush,’ the second the ‘soft hit.’” He explains that in the former, everyone in the vehicle is shot dead in order to make a statement of protest; in the latter, people are robbed or maimed but otherwise left alive. “Soft hits,” Vital assures me, “are the better ones.”

We pass through frequent RCD roadblocks; at each one, the park warden or government monitor leaps out of the van to shake hands and cajole the officer on duty. The notion of our going to see the gorillas always creates a profusion of laughter. I stay in the back of the van, by the window, returning the stares of children who have the stoic, circumspect countenances of adults. Only the very youngest give emphatic waves or smiles, and the soldiers mock their earnestness.

Our minivan groans and perseveres down the boulder-strewn tract past small villages of round thatched huts and banana trees. Women walk along the road, wearing wraps of printed cloth and carrying washtubs or cords of firewood on their heads. They are not the least bit interested in my presence in the passing van, in the strangeness of a white woman out here. Rather, their eyes settle nervously on the RCD soldiers inside, a shock wave of fear passing over their faces. All you can taste in this country is fear. An inescapable vortex of it. I hope these gorillas will be spectacular, more fantastic than anything I could have imagined.

We near the Virungas, stopping periodically so that the soldiers inside can hop out to extort taxes from someone walking along the street. I can see mountains of jungle rising from a series of deforested foothills. The land resembles a crude checkerboard: square, empty fields baking in the sun. With no buffer zone between pastureland and jungle, there is nothing to prevent further encroachment into the park. Farmers and refugees have cleared the jungle up toward the cloud line; the gorillas now very much inhabit the mists.

We reach the end of the road and park the van at an outpost called Jomba. Only two weeks ago, the Interwahamwe came through this area, which perhaps explains why nobody is out tending the fields. To reach the Jomba park headquarters, we begin a long hike uphill through grassy, deserted fields. “In 1994,” Vital says to me, “these fields were covered with jungle and giant trees.” Ten years ago, Vital worked here for a large, five-star tourist lodge—it is now the pile of pillaged, burnt-out rubble that we pass on our way up. It is hard for me to picture this place as a stable environment, with foreign tourists resting on lawn chairs and sipping cocktails before a majestic view of the Congolese Virungas.

Jomba headquarters—a collection of a few small shacks—sits on top of a lonely, tree-stripped hill at about 7,500 feet with the jungle-covered peaks of the volcanoes acting as backdrop. It is a vulnerable spot in which to live, with no immediate cover and an imposing spread of jungle nearby that might hide militiamen, snipers, ambushers.

When I reach the round cement building that acts as the base, a group of men in olive-colored uniforms comes out to greet me: the park rangers. They smile shyly; it is not often that they receive visitors, particularly foreigners. These men confirm what I already know: no one is paying them anything. Not the government in Kinshasa, capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, and certainly not the RCD. During better periods, they receive funding from UNESCO, which allows them to feed themselves and provide for their families. But it barely suffices. It is these men who have lost 82 of their own in the past few years. I’m shown the bloody photo of one of their most recent casualties, a man named Jean de Dieu—John of God.

While gorilla populations in Rwanda and Uganda have slowly climbed in recent years as a result of conservation efforts, most experts agree that the number of mountain gorillas in Congo has dropped significantly. They have been caught in snares, hunted with impunity by poachers, or killed in crossfire. An estimated 15 to 17 individuals have been killed since the war started. For such a fragile population totaling only about 355 in all the Virungas, a loss of 15 to 17 members is dramatic. “If you kill only 10% of them,” says Tony Mudakikwa, senior veterinary officer for the park authority or Rwanda, “and that’s only 35 individuals, I can’t imagine they’d have the genetic viability to survive extinction.” It is already a concern as gorillas are starting to be born with webbed fingers—a sure sign of inbreeding.

Dominique Bavukai, chief of patrols for Jomba since 2000, says that just a few months ago one of his men was kidnapped by the Interwahamwe and never heard from again. A week later, the same Hutu militiamen attacked the station again. A lengthy firefight ensued, but the rangers were able to hold them off. Still, they lost another man during the battle.

“No one knows where the enemy is,” Bavukai says to me, and he glances out of the hut at the surrounding countryside. His eyes look weary, resigned. “But our mission is to protect the gorillas as long as they are at risk of extinction.”

“Some people in my country might wonder why you don’t get a safer job,” I say to the men. “Is there a reason why you’ve stayed?”

I am hoping for a certain kind of answer, I realize. A lofty answer about wanting to preserve the heritage of the mountain gorillas for future generations, about the inherent grace and beauty of a creature that must be saved at all costs. But Bavukai’s reply is practical rather than poetic: “There are no other job opportunities out here in this war zone. It would be hard to just quit this job and find another.”

*

Our long column snakes its way toward the jungle and the gorillas, through barren farmland overtaken by weeds. Each soldier holds his AK-47 on a shoulder, fist around the muzzle, camouflage uniform flapping around his thin frame. The higher we climb, the closer the clouds come to touching me, peppering my face with mist. We finally approach a thick jungle

that stretches to the very tops of the volcanoes, an unbroken spread of primeval green.

Some trackers who monitor the mountain gorillas walk over to greet us. They are stationed far from the Jomba site, on the edge of the jungle, completely vulnerable to any roving bands of Interwahamwe guerrillas. We all head into a mass of trees and vines that requires more pushing and shoving than actual walking, the men hollowing out a path with machetes. The head tracker waves to me, and I follow him into a grassy clearing. I’m so busy looking around that I nearly walk into a giant silverback named Rugendo. He is lying on the ground, his chin resting on his hands, staring at me with liquid brown eyes. He is gigantic—his shoulder span alone is wider than two grown men’s—and his enormous face studies my own with eye-blinking fascination. Two of his females, smaller and furrier, seem paralyzed with wonder as they gaze at me through the bamboo.

I kneel down and stare at them all. “Hello,” I whisper, our eyes meeting.

The mountain gorillas are the only gorilla species that can be habituated to a human presence. Inexplicably. It is this innate trust that fascinates me. With what other wild animal can a person readily gain such close, intimate access? Surely this helps explain why so many tourists will fly halfway around the world for a mere hour’s visit with these creatures, and why, through war and famine and unrest, so many individuals and organizations are determined to save them. But there is something beyond this: these animals, with their trusting and peaceful natures, caring family units, and unconditional acceptance of others, reveal to us humans just how far we’ve strayed.

The females come toward me, slowly at first and then faster as the tracker attempts to wave them off with a stick. They are determined to touch me. The tracker tries to explain their strange behavior—“They haven’t seen a white person before”—but I’m not sure I believe him. Rather, they seem to want to greet me, welcome me. The females regroup for another approach, but the tracker is too fast for them. He explains that the gorillas are at risk of catching human diseases, and so only researchers, who are quarantined for two weeks upon arriving here, should interact with them.

Rugendo rolls onto his back—his enormous pot belly facing up, his legs splayed and toes wiggling—and yawns. Casually, he grabs some young bamboo and gnaws on it, glancing peacefully at me and the trackers as he chews. Humans could do anything to him right now, but he simply scratches his great belly, farts, and sighs, closing his eyes to us.

I can only wonder what will happen to him. Two weeks ago the Interwahamwe crossed through this park, and they will cross through it again.

My hour is up, and the females take one more daring advance toward me before the tracker intervenes and shoos them away. Reluctantly, I follow the men out of the jungle, back into the desolate fields.

*

Dr. Theogene Rudasingwa, Rwandan President’s chief of staff, sits calmly in the heavily guarded presidential compound in Kigali, fingertips touching lightly. When I ask him about his country’s commitment to protecting the gorillas, he says, “Our agenda, first and foremost, is to protect the people. The protection of the mountain gorillas has been at the back of our minds. But it’s in our interest—and the gorillas’—to establish more security in Congo and Uganda, as well as Rwanda.”

In the name of “security,” Rwandan and Ugandan troops first entered Congo (then Zaire)

in 1996, igniting its bloody civil war. Rwanda pulled out its troops in 2002, but not before establishing local armies and governments—such as the RCD—to do its bidding. Uganda soon followed suit. The two countries now battle each other through proxy armies for control of Congo’s lucrative natural resources.

The worst of their playing fields is in eastern Congo’s Ituri Province, where Uganda and Rwanda frequently flip-flop in supporting the militias of the Lendu and Hema tribes, who busily engage in tit-for-tat massacres with each other. At least 50,000 people have died since hostilities began there in 1999, most of them civilians; half a million others have been displaced. Various relief organizations characterize this conflict as an all-out “genocide,” in which rebel groups take the machete to anyone—man, woman, or child—with the wrong ethnic identification. Little wonder that the mountain gorillas are at the back of the Rwandan government’s mind.

I decide to go to Ituri Province, to the epicenter of the violence, to see how bad it is. Whatever happens there can have a domino effect on this whole region, destabilizing entire countries, killing untold numbers of people, and bringing species caught in the middle—like the mountain gorillas—to extinction.

III. Bunia, Ituri Province, Eastern Congo

“Hey, journalist! I will kill you, journalist!” The boy looks at me with blood-colored eyes—he could not be older than nine or ten—and waves the muzzle of his AK-47 at my face. He is drugged up, gone. He wears a red T-shirt and a sardonic grin, his camouflage pants new and stiff-looking, hanging from his body like oversize pajamas. The back of the truck is full of others like him, child soldiers: a 13-year-old with a rocket launcher, a couple more teenagers with assault rifles. The driver, another kid, grinds the gears of the stolen Toyota, trying to learn hands-on how a manual transmission works. I pause on the side of the street, intent on not showing fear. Fear is what they want, these children in control of Bunia. Show a trembling hand, throw a sidelong glance for assistance, and this weakness instantly registers in their brains. You can see the grins widen, the hands tighten around the weapons. They know they have you.

But these boys are busy with other matters. They have a truckload of looted furniture to take somewhere, and so the truck jumps into gear and roars off down the pitted street. I watch them go, still not moving. Only when they are safely out of sight do I let out my breath.

“Jesus,” I whisper.

Further up the street, a United Nations peacekeeper in a light-blue helmet and a flak jacket—a Uruguayan soldier—sits on top of an armored personnel carrier, elbow resting over the stock of his machine gun. Watching. These 700 peacekeepers, primarily Uruguayans and none battle-tested, aren’t mandated to interfere militarily unless U.N. personnel or property are directly threatened. They remind me of actors going through the motions of soldiery. But they are not unaware of their impotence: a number of them, obligated to simply watch the unraveling slaughter, have gone insane and been evacuated.

Since the peacekeepers’ arrival in April 2003, civilians have continued to be killed within sight of the U.N.’s main compound; rebel soldiers have been seen adorning themselves and their weapons with the organs of their victims. Cannibalism is rife; militias go into the jungles to hunt the local Pygmy population for “bush meat.” A week ago, the Rwanda-backed UPC (Union of Congolese Patriots) guerrillas, who are allied with the Hema—those who just wrested the town of Bunia from the Uganda-backed Lendu—tossed a mutilated corpse into the U.N. compound to remind the peacekeepers of their uselessness. Each day, more stories of mass killings and atrocities reach the U.N. ears in Bunia, while hundreds of refugees pack into its makeshift camps and hospitals with their limbs cut off or their bodies shot up, telling the same gruesome stories: how family members were killed in front of them, how they were forced to eat their own flesh. The U.N. does nothing. It will tell you that its hands are tied by its Chapter 6 Mandate forbidding military intervention—a mandate that was approved by member countries, thus underscoring international reluctance to do more.

The question of who’s to blame for this mess leads one down a lengthy historical path of culpability. The Hema and Lendu peoples lived relatively peacefully together for centuries in Ituri until the Belgians colonized Congo and declared the Hema as racially superior, thus justifying the use of Lendus for slave labor. When the country gained its independence in 1960, the favored Hema ended up in charge of Ituri’s land, businesses, and government offices. This created growing enmity between the two groups, but tensions escalated to wholesale violence only after Western powers discovered that Ituri is home to the largest gold reserves in the world.

I enter one of the makeshift hospitals run by Doctors without Borders. It sits on the outskirts of Bunia near the airport, adjacent to a large refugee camp full of people—mostly Hema civilians—who are lucky to have escaped their Lendu attackers alive. In two large rooms, the walls are lined with foam mattresses, most of which are occupied by children and adults in bloody wrappings and casts: the victims of machete or gunshot wounds, land mines, mortar fire. The head of the DWB mission here, who for political reasons asks that his name not be used, tells me that a handful of doctors are doing 120 to 150 new consultations a day, a staggering 3,000 a month. The Doctors without Borders physicians and staff look haggard, yet the sheer numbers of new patients keep them almost constantly on the move, forcing them to send even the worst casualties on their way after a few days.

I meet a 70-year-old woman missing her left arm and leg. She is in shock, which is to say, she looks at people without seeing them, her eyes wide and gazing at the world with uncomprehending helplessness. When my translator, Jean Jacques, kneels beside her and asks what happened, her eyes graze over him as if he were formless, an apparition. He must ask the question a second time, and she answers in a mumble, as if talking to herself.

“She says she was hit by an explosion,” he tells me. “From the sky.”

A bevy of doctors and assistants surrounds her bed. I watch as an aide unwraps her

bandages. The last portions are stuck to her wounds, and she lets out a long cry as they are torn off, looking through each of the people around her. Where will she go? I wonder. What will she do? The doctors, facing an onslaught of new patients, quickly redress her wounds and move to the next bed.

I leave the hospital and start walking down Bunia’s gutted roads, past decaying buildings riddled with bullet holes and the emptiness of side streets that speak of something hushed and awful. It is as if death leers at me from every direction. It stares out at you from the faces of the refugees in the tent camps. You hear it in the voices of the child soldiers roaring by in their stolen trucks. You smell it in the cholera-infested latrines and on the disinfectant-coated floors of the makeshift hospitals. In Ituri, to the rampaging rebel soldiers, life isn’t cheap—it’s irrelevant. They claim a monopoly on it, decide who lives and who dies based on the lottery of their mood.

I think back to the people trying to save the mountain gorillas. How seldom I heard them mention the region’s human casualties. There seemed to be a rejection of an all too common premise: that a human being’s life is more valuable than any animal’s. People here have explained the carnage to me as a “loss of humanity,” of humans becoming “animals.” I remember Rugendo, the silverback I met in the Virungas. No: we do not become animals. We become the worst that is in ourselves, what is purely, unequivocally human.

*

The question of who’s to blame for this mess leads one down a lengthy path of culpability. The Hema and Lendu peoples lived relatively peacefully together for centuries in Ituri until the Belgians colonized Congo in 1908 and declared the Hema as racially superior, thus relegating the Lendu to a permanent lower class status and slave labor. When the country gained its independence in 1960, the favored Hema ended up in charge of Ituri’s land, businesses, and government offices. Enmity grew between the Hema and Lendu, but tensions escalated to wholesale violence after Western powers discovered that Ituri is home to some of the largest gold reserves in the world.

I meet with Colonel Daniel Vollot, commander of U.N. forces in Ituri. He is a tall, middle-aged Frenchman with a crew cut and a wiry frame, looking in every way like the career soldier. I repeat to him one of the most blaring allegations made by Rudasingwa, the Rwandan president’s chief of staff: that Interwahamwe responsible for the Rwandan genocide are now “linked to Uganda” and are finding “safe haven” in Ituri. This is news to Vollot; he says he’s seen no evidence of it. But when it comes to finger-pointing in this part of the world, the veracity of claims is immaterial as long as they do their job, get the blood boiling. Vollot is not an optimist; he has an unmistakable look of defeat in his eyes. After he describes a U.N. plan to send a thousand French troops here with a beefed-up mandate that authorizes the use of force, he quickly shoots it down: “We can’t solve the problem of pacifying Ituri with a thousand troops. And one thousand is more than in Kosovo, more than in Sierra Leone.”

As we speak, I think of all the civilians being maimed and massacred across the countryside. “Doesn’t it bother you,” I ask Vollot, “that all of these atrocities are going on right now and you can do nothing about it?”

“Yes, it’s frustrating!” he declares. “But I can’t change the world. I do my best here. The press’s negative comments about our mission in Congo—it’s scandalous. Every day we do our best.”

The U.N. information officer who has been monitoring our interview stands up now,

trying to end it. Vollot ignores her and leans close to me: “There was an old woman, 85 years old, who was brought in with both her arms cut off. Eighty-five years old. Sometimes I want to kill. Really. I tell you I’ve seen a baby with its neck cut. Two babies with one cut.” He demonstrates for me, drawing a pretend knife across his chest. “Now, I’m like a beast. It’s not a problem for me. I see it, I get used to it. But that’s not normal behavior. Whenever I leave this country—if I leave this country—when I have a normal life, all of these things will begin again in my brain. This will be very difficult for me, I’m sure.”

*

I arrange to go on the U.N.’s Alpha Route patrol to the north of Bunia, in the company of three military observers: an Indonesian, an Indian, and an enormous Zambian, nearly seven feet tall, who has surely missed his true calling as a linebacker. My request was reluctantly granted: U.N. officials told me that it would be bad press if a journalist was killed by rebels, especially after two of their own monitors had just been slaughtered in the Ituri countryside, their hearts and livers eaten by the assailants.

The observers give me a light-blue flak jacket and helmet to wear, and I get into the backseat of their Toyota 4Runner. With the Indonesian driving, we pass through the razor wire barriers protecting the U.N. headquarters, entering the long main drag of Bunia controlled by the omnipresent UPC child soldiers. Noticing that none of my companions has a weapon, I mention this to the observer from India.

“We can’t use weapons unless we’re defending ourselves,” he explains. “It’s against our mandate.”

“Yes,” I say. “So why don’t you carry weapons to defend yourselves?”

“We do not want to be seen carrying weapons. It will give a bad impression. We want to remain neutral.”

“We have this,” the Zambian says, holding up a radio. “We can call in if we have trouble.”

“You can call in so they know where to pick up your dead bodies,” I say, half joking.

But the Indian nods. “That’s right,” he says. “So they can get our bodies.”

We drive past the airport, leaving behind the U.N.’s radius of protection. With no jungles around Bunia, we enter rolling green grassland, following a dirt road that curves to the north. A large contingent of Lendu fighters is supposed to be massed behind some approaching hills, regrouping in order to try to retake Bunia from the UPC-backed Hema. The Indian explains to me that his patrol has orders to conduct “reconnaissance” to find out more about this gathering from the locals.

We pass a man riding a bicycle, and the Indonesian stops our vehicle and flags him down. “Him,” he tells us. “We will ask him.” But the three men just look at one another. It turns out that none of the peacekeepers speaks French, the only means of communication with the local people. I am assuming the U.N. commanders knew this when they sent these men out—yet, inexplicably, here we are. Ours is a situation as asinine as deploying 700 Uruguayan—Spanish-speaking—peacekeeping troops to a francophone country.

The Indian turns to me. “Do you speak French?” he asks.

“Somewhat,” I say.

“Good. You can be our interpreter.”

I find it unsettling that any potentially critical information for the U.N. must rely on my

French language skills, but I give it my best shot. I ask the man if he’s heard anything about the Lendu, inquiring about numbers of fighters, possible troop movements. He says that, for sure, a large number of them, perhaps as many as a thousand, are gathered behind the hills, but to his knowledge they haven’t started moving forward yet.

The Indonesian stops me. He’s angry. “What are you asking him?”

I tell him.

“Don’t ask him that,” he says.

“I thought that’s what you wanted to know.”

“We’re only supposed to ask them, ‘What’s the situation here?’ Do not mention Lendu or troop movements.”

“We want to stay neutral,” the Indian explains.

When we stop another man on the road, I ask only what I’m supposed to ask: “What’s the situation here?”

The Congolese man looks at me, puzzled, then gestures around him. “It’s fine,” he says.

I tell the Indonesian.

“Good,” he says. He turns the vehicle around and we head back to town.

*

Each evening I run the usual two-block gauntlet from where I’m staying—a room in the guest house of some Belgian priests—to the U.N. compound and then back again, passing down the pitch-black streets of Bunia, never knowing who or what waits in the shadows ahead. I’m reminded of childhood games of tag. My senses become sharp, fixed on sounds and sights. If I see UPC soldiers coming, I step behind a tree or the corner of a building and wait for them to pass. I have become a gambler, wagering my safety each night on the whims of the soldiers and their sporadic gunfire cracking across the otherwise silent town.

Tonight I have made it once again to the U.N. compound. If this is a game of tag, then the goal is the armored personnel carrier sitting on the lit-up corner before the rows of razor wire. By now, I recognize the Uruguayan soldier on top, and he invariably greets me with a smile and a wave from behind his .50 caliber machinegun.

“Hola!” another soldier calls out from aboard the APC.

“Hola,” I say to them, relieved to be near them and their guns. “Qué tal?”

Whereas during the day these men stick stoically to their job, the nights are different. The darkness, its increased danger, does something to them, turns them into consummate flirts. They will ask me quick questions, delighting in my lousy Spanish, then watch me head to the gate of the U.N. headquarters for my meeting with the information officer, who often doesn’t receive news reports until evening. When I return afterward and pause again before their APC, they greet me as usual, only this time I have lost my enthusiasm to talk with them: before me sits the long black corridor to the safety of Father Jo’s place, two blocks away. Two interminable blocks of darkness.

I start walking quickly down the street. I’m hoping the Uruguayans will keep watching me, will break their mandate and come to my assistance if I run into trouble, but it isn’t long before their white APC becomes barely discernible behind me. I hear voices. Some young UPC soldiers step out from a building, see me, rush over and surround me. I remember the U.N. warnings: that the rebels want to capture or kill foreigners. These men—drunk, drugged-up adolescents—ask for cigarettes or money. I glance behind me, can see the Uruguayan soldier behind his machinegun, but does he see me? Do I yell out? But that would be revealing my fear to these men. I keep walking, the soldiers forming a pack around me, demanding money.

“Okay,” I say to them.

I pull out a wad of dirty Congolese bills and shove it into their hands. An argument erupts, and I use the opportunity to shove through them, run to the priests’ compound, and bang on the metal gate. A caretaker opens it. The game is over for tonight. Safety.

*

If most of the people in Ituri have “lost their humanity,” it is all the more remarkable that the two Belgian priests have managed to cling so strongly to theirs. Father Joseph Deneckere—known as Father Jo—is a legend here. I do not exaggerate: he has a saintly light in his eyes. Age 58, he’s lived in Ituri for going on 33 years. He and his colleague, Father Jan Mol, are the only foreign priests to stay on in Bunia through all the chaos and killing. Father Jo has been threatened numerous times, but he earned a reputation as someone to be reckoned with when some soldiers burst into his compound and trained their guns on him. They decided to play with him before they killed him, so they shot bullets around his head, made him temporarily deaf. In what Father Jo describes as a moment of heavenly intervention, he gained superhuman courage and strength, grabbed the burning-hot muzzles of their AK-47s and tossed them aside, and yelled at the soldiers like a schoolmaster chastising pupils. As he puts it, “They became afraid of me because I was not afraid.” Father Jo is now known throughout the countryside as the White Father who tossed death’s guns aside.

He is a large, gray-haired, bespectacled man who can be found at the end of each day

holding his usual cigarette and bottle of beer. He and Father Mol maintain a guesthouse with impeccably clean rooms, as well as a flower and vegetable garden, and a chapel in which a black Jesus on a cross gazes down with wincing eyes. Father Jo knows every local tribal language fluently, speaks to victim and perpetrator alike with a gentle hand on their wrist. He is endlessly patient, tolerating the demands of the strung-out journalists staying at his place, shrugging it off when they noisily enter the compound after curfew, reeking of whiskey and Primus beer. And he sits for long interviews, giving the same answers again and again to the usual questions from the stream of reporters who come and go. Why such chaos in Bunia? What happened?

I am curious about other things, though. For example, how Father Jo keeps that light in his eyes, given all that he’s seen. Two weeks ago, two Congolese priests in Bunia, along with 20 refuge seekers, were trapped in a building surrounded by Lendu attackers preparing to kill them. One of the priests phoned Father Mol, begging him to send U.N. troops to his assistance. Father Mol tried, could not persuade a hamstrung Colonel Vollot to break his mandate, though the priests were only a half-mile away. The result was 22 people dead, most of them killed by machete. Five hours after Father Mol’s frantic appeal, Father Jo accompanied Father Mol to identify the bodies. There were men, women, and children.

“I often ask, ‘Where was God?’,” Father Jo tells me. “I think God was not in that killing. God gave the world to mankind, and if we follow the gospel of charity and love, it must go good once more. God is love.”

But he admits that his faith has been tested. He tells me Thomas Lubanga, head of the UPC rebels, once was a seminary student, had wanted to become a priest.

“How do you explain this?” I ask him.

“People here believe they will be killed, and so they do the same thing to others that

they’re afraid others will do to them.”

Father Mol offers his own explanation, his words coming out with slow deliberation. I can tell he has thought about this many times. “Do we ever convert people really? The light and darkness are always present in a person, and there are moments when the bad things are reigning more strongly than the good things. These soldiers, warlords, are all victims of the political and social situation here. What is good and what is bad? I think that humiliated people will react by doing horrible things. They’re asking, ‘Can we be recognized as human beings?’”

*

The next morning, I hear news of a Cessna that has arrived in Bunia and is bound for Entebbe, Uganda. I have no business in Uganda, and Entebbe is a long way off, but I ask a U.N. official to give me a lift to the airport so I can get a seat. Anyplace in this world seems better than being in Bunia. While I wait for the pilot to finish up his business, I see the head of the Doctors without Borders mission overseeing the unloading of supplies from a cargo plane. He recognizes me and comes over to say hello. I notice how old his face looks, how grave, though he’s only in his 30s.

“So you’re leaving,” he says.

“Yeah. I’m running out of my nine lives.”

He nods. “Yesterday,” he says, “we had to amputate a girl’s arm. We had to wait an hour with it because we weren’t able to bury it. The arm was just sitting there in the bucket—we tried not to look at it.” I don’t know why he decided to tell me this; it is as if he were telling me about the weather. I wonder how long it will take before he allows himself to feel again.

“Is this the worst you’ve ever seen, here in Bunia?” I ask him.

“No. I was in Angola. Liberia. Sri Lanka.”

“So do you think there’ll be peace here?”

“I don’t like to lie,” he says. “No.”

The pilot is heading toward the Cessna, so I say goodbye and get in the plane. We taxi down the runway and surge into the air, but the dangers are not over yet: the pilot must gain a high altitude and avoid flying over roads or villages to protect us from any anti-aircraft fire. Gradually, Bunia and its problems shrink below us. I see that it’s better to view this land from afar, muted by clouds and distance. Then I can pretend there’s beauty, at least. I can forestall heartache.

*

Back in Volcanoes National Park, I sit high on a slope of jungle, watching a family of mountain gorillas climb down from their trees to greet us humans. Some British tourists, perched farther below, wave their camcorders around like frenetic conductors as they try to capture their first communion with these animals. Each person has flown all the way to Africa and spent $250 for this one-hour visit, but from the awed look on their faces they’re obviously not disappointed.

I rest above them, out of the way. A gorilla baby beats his chest at us and swings from a branch. Trackers busy themselves with cutting a path higher up the slope, hoping to lead us to the silverback father. I recall a photo I saw of a gorilla touching Dian Fossey: the first physical contact this species had ever made with a human being. Fossey’s face had looked radiant, blissful. She had stepped outside of herself. You could tell from looking at that picture that she

would never be the same again.

I am so busy recalling that image that I don’t notice a female appearing from the brush nearby and coming directly toward me. The trackers haven’t noticed her either, and they yell and rush up the slope. But it’s too late. She’s nearly reached me, is as large as I am, with long, wild black hair, a wide, flat nose, and those liquid brown eyes. I have never been this close to a wild animal before, and I don’t know what to do. Fear rushes through my body, and I freeze, holding my breath. She ambles forward on her knuckles and stops just inches away from me, her eyes running over my face. (As if from some other universe, faint and distant, I can hear the trackers scream and scold me—still, I can’t move.) All at once, she raises her arm and rests a black, clammy hand on my cheek.

The head tracker yells—he is a few feet away now—and the gorilla (her name, I learn, is Mbere) promptly drops her hand and retreats toward a break in the forest.

I watch her go, discovering that there are tears in my eyes. As a young baby climbs up the slope ahead of her, she stops to take an enigmatic look at me over her shoulder. If I could, if it were not already too late, I would follow her back into the state of wonder.

|

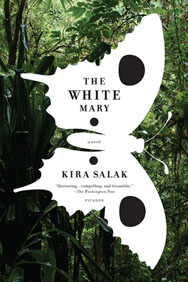

THE WHITE MARY

by Kira Salak

"A gripping debut novel."

Publishers Weekly Pick-of-the-Week

"There aren't many books that we hand to friends, urging,

'You have to read this.' The White Mary is one of them."

Cleveland Plain Dealer

"Riveting."

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

"With The White Mary, journalist Kira Salak makes a stunning

debut as a novelist. This is a story whose beauty and power

sweeps you along, like the jungle rivers that bear her heroine

into the heart of New Guinea in search of a vanished American."

--Philip Caputo

|

© 2008 Kira Salak, KiraSalak.com--all rights of reproduction in any form reserved

![]()