MINING FOR MIRACLES

(published in National Geographic in slightly different form)

People come to Basin, Montana looking for miracles: cures for rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, depression, cataracts. You name it. From the highway, though, the tiny town doesn’t seem to offer much. Just one exit to take, and a single long look shows all there is to the place: a collection of weathered houses and old miners’ cabins huddling close to the interstate, caught between the high peaks of the Elkhorn Range. Basin looks like a place left behind on a whim. No stoplights, no gas stations, no grocery stores. Were it not for its world-renowned radon “health mines,” Basin, population 300, would probably vanish back into the mountains as quickly as it came, leaving highway passersby to marvel over why anyone would live there.

Prospectors founded Basin in 1880, when it was nothing more than a collection of clapboard brothels, pup tents, and gritty saloons in a Montana that hadn’t even graduated to statehood. Law and order depended less on rules than on the strength of a man’s fist.

“They were a tough bunch of people and they all liked to fight,” says 68-year-old “Happy” Bullock. “There were cowboys on one side and miners on the other.” An “old-timer,” Happy claims Basin roots that go back three generations. He settles himself in his chair in the Silver Saddle Saloon and examines me with the patient stare of a man who’s seen more than his share of newcomers.

“Did you like to fight?” I ask him.

He gives me a slow grin and winks his eye. “A little.” Laughing, he tugs at the brim of his cowboy hat. “We were boomers, looking to make a fortune. What you did is, you hollowed out a mountain and walked through it. I shipped 35,000 tons of gold and silver from my mines.”

You can still see evidence of Basin’s early mining heyday at the end of the 19th century if you know where to look. Hike up in the hills and you practically stumble upon tunnels abandoned during the gold fever search for bigger and better. Graves of Chinese laborers lie in unmarked mounds along Basin Creek, while ghost towns stare down on Basin from the high hills. Why did Basin survive? Local legend explains it this way: Someone once put up a small sign along the highway that said, “Basin—Heaven.” If you saw the sign, you’d end up in Basin for life. Almost like a spell. “Every time someone crazy comes to live here,” one resident says, “we say, ‘Oh, they must have seen the sign.’”

Plenty saw it over the years. Hippies flocked to Basin in the 1960s to bring peace, love, and happiness to the rough-and-tough miners, loggers, and cattlemen. Then the bikers came, only to be kicked out by locals who burnt their house down. Finally, there came the artists. Patrick Eckman turned a neglected church into his Basin Creek Pottery Studio, while jazz singer M.J. Williams and her partner Nan Parsons refurbished an old bank and created the Montana Artists Refuge. The Refuge now attracts artists of international reputation, and plans to bring Tibetan tangka painters to stay in Basin’s wild woods. A lot has changed.

But then again, a lot hasn’t. Take “Mountain Man” Gordon Ford, who lives up in Basin’s mountains at 7,300 feet. A “homesteader,” he and his wife Janet survive off the land in a log cabin they built themselves. Elk skins stretch out to dry in their front yard. Inside their cabin, Janet prepares chokeberry jelly, weaves wool blankets, and creates Native American art that she hangs from rafters.

“Once every two or three months, I make a big trip into town,” Janet says to me, “town” being Basin proper. The Fords live only nine miles out, but that’s nine miles by mountain standards, which means four-wheel drive travel through deep snows and spring washes. At 7,300-feet up, their winters stick around ten months of the year.

I ask Gordon what’s appealing about mountain living, and he leans forward, stroking his long, gray beard. He looks at me with the clear blue eyes of a sage.

“Peace,” he whispers. He says it so softly that I can barely hear him, as if he were telling me a secret he doesn’t want getting out. “Peace. Your whole being changes up here.”

Gordon is living proof of Basin’s live-and-let-live spirit, where folks largely do as they please. Back in town, stray dogs, said to be as numerous as Basin’s inhabitants, trot along the muddy main street, while horses graze on the playground of Basin’s only school, first built in 1895. It is here that twenty students, grades K-6, study in the same one-room classroom where many of their grandparents did. Each day at 8a.m., teacher Tammy Urich calls her kids to class the old-fashioned way: by ringing a school bell. In a place as small as Basin, everyone can hear it.

I look for that special sign along the highway, but only see the ones advertising the Merry Widow and Earth Angel Health Mines. Basin is the site of two of the world’s handful of radon mines, which have attracted people by the hundreds of thousands since the early 1950s. Some scientists and lay people claim that spending ten days in the mines, breathing radioactive gas, drinking radioactive water, will cure you of a whole host of ailments. It sounds incredible, I admit. But intriguing, too.

The owner of Earth Angel, “Wild Bill” Remoir, a WWII disabled veteran, goes into the mine every day with his dog, Stub.

“Now I seen a dog go in that mine that couldn’t hardly walk,” he says, “and by about the second day he was chasin’ rabbits. That was my rabbits that he was chasin’.”

He’s referring to his more than 120 pet rabbits that live on the mountainside around the mine—big black ones, brown ones, floppy-eared ones. When he leaves his trailer, they all hop over and flock around him as if he were a latter-day St. Francis.

“Lady, I’ve seen miracles go through this mine here,” he says, pointing to the 600-foot-long tunnel that cuts through the granite bowels of the mountain. “But what does it? I don’t know. Now I cannot see the radon in there, and I cannot smell it, and neither can I see the good Lord nor smell Him neither, but there’s something in there that does ya good.”

Dwayne Knutzen, the owner of the Merry Widow Mine, offers me a more scientific explanation. He talks about “radiation hormesis”: the use of low-dose radiation to treat and cure diseases of the immune system.

“What happens is that as we age, cells start deteriorating and our immune system wears down,” he explains. “Low-dose radiation stimulates those cells to get back in the game again. The dose makes all the difference. A little’s good for you, and a whole bunch isn’t.”

Jerry Cutler, a leading expert on the effects of low dose radiation on the human body, further explains: “All organisms have natural defense mechanisms, which prevent, repair, and eliminate cell damage. Low does of radiation stimulate our natural defenses, while high doses impair them. Cancer and other diseases can be treated with low dose radiation.”

Still, most scientists and lay people in the U.S. finds such claims unsettling, given the well-documented ill effects of high-dose radiation on the body. Yet, ever since the Merry Widow became a “health mine” in 1952 when studies showed the positive effects of low-dose radiation on the body, hundreds of thousands of people have come to Basin from as far away as Japan, Germany, and Canada to walk 450 feet into the mines to sit for one hour “treatments” of low-dose radiation, three times a day. Their signatures and messages cover the rock walls, testament to the great many who have found relief here. Old bus seats line the sides of the mine to provide seats for the daily crowds of 50 or more people during the summer months, with one passageway leading to the “Doggie Den”: a cubby-hole with built-in shower, where you can bathe yourself and your arthritic dog. At the end of the tunnel, by a series of spigots, I find people soaking their hands or feet in basins of the frigid 50 degree radioactive water, which they believe to be more beneficial than just breathing in the radon gas. A rack of magazines and board games help visitors pass the time, their conversations creating a pleasant rumble down the mine shaft.

Being in these mines is like entering an odd sort of club in which everyone greets you with nods of congratulations and knowing. Because, they will tell you, miracles have occurred here—and not just to the faithful or the lucky, but to unbelievers as well. Everyone, it seems, feels better when they walk out ten days later.

“In here’s the nicest bunch of sick people you ever met,” Clyde Schuster says. Aged 94, from Napa, Idaho, he’s been visiting the mine every year since 1962, when he says it completely cured his rheumatism. The skin of his face looks as supple and ageless as a baby’s.

“I was a nonbeliever at first,” says Clyde’s grand-niece, Sue, who first visited the mine eight years ago. “I just came along with my Uncle Clyde for a vacation. But when I got back from the trip, my migraines were gone for good—and I’d had migraines for most of my life.”

Sue collects clay from the walls of the mine, swearing that it heals skin infections. Most visitors end up taking some of the mine away with them: lichen or mold, water, mineral secretions—even little pillows filled with radioactive gravel. One man is said to have loaded up his truck with a hundred gallons of water for his racehorse. Whatever works.

For Rita Klapan, who has suffered from severe osteoarthritis since age 30, the mine has granted her a new life. “The doctors had given up on me,” she says, tears in her eyes, “and I didn’t want to go into a wheelchair. I heard people talk about the benefits of these mines, and I said, ‘Well, I’m going to give it a crack.’” Six years and several mine visits later, her illness has halted, the pain has left, and she can walk without crutches.

Stories like Rita’s brought Tanya Beck to Basin, all the way from Duluth, Georgia. Her four-year-old daughter, Allison, suffers from progressive rheumatoid arthritis; her doctors, out of solutions, are filling her with chemotherapy drugs, predicting she’ll spend her life in a wheelchair.

“This seemed like our last hope,” Tanya says. “When we got here to the mine and I saw what it was, it was kind of like a Twilight Zone thing. I thought, there’s no way. But Allison is running and playing now. She hasn’t been hurting. She’s definitely getting better, and this mine has something to do with it.”

The other mine-goers and I have been listening to Tanya raptly. We all hope it’s true, that Allison is getting better. For the first time, I get up to drink some of the radioactive water along with everyone else. I figure it couldn’t hurt.

|

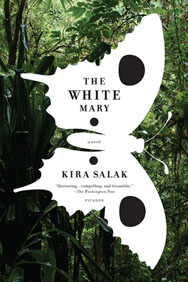

THE WHITE MARY

by Kira Salak

"A gripping debut novel."

Publishers Weekly Pick-of-the-Week

"There aren't many books that we hand to friends, urging,

'You have to read this.' The White Mary is one of them."

Cleveland Plain Dealer

"Riveting."

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

"With The White Mary, journalist Kira Salak makes a stunning

debut as a novelist. This is a story whose beauty and power

sweeps you along, like the jungle rivers that bear her heroine

into the heart of New Guinea in search of a vanished American."

--Philip Caputo

|

© 2008 Kira Salak, KiraSalak.com--all rights of reproduction in any form reserved

![]()