IRAN: INTO HOSTILE TERRITORY

(published in National Geographic Adventure; Winner of the 2007

Lowell Thomas Gold Award for Best Foreign Travel Article)

If you are an American traveling to Iran, of course you want to visit the United States Embassy. You must see it. Consider it. It was the place overrun by young Islamic revolutionaries in 1979. The place where 52 blindfolded, manacled embassy personnel were paraded in front of the international community for 444 days by student militants. It’s the place that saw the end to all diplomatic relations between the two countries, ruining President Jimmy Carter’s chances for reelection and ushering in the Reagan Era. It’s here where, as an American in Iran, you realize how special you are—that you’re a member of that bizarre, intriguing fraternity known as the Great Satan.

“My European clients don’t ask to see this place,” my guide says to me unhappily.

He doesn’t understand the reason for my coming here. To him it’s merely an inconvenient, unpleasant place to visit, overrun with secret police who don’t appreciate tourist calls—especially not by Americans. Should I get out of the van to take a photo, there’s a chance my camera would be confiscated and I might even get arrested. In which case he’d be obligated, as my official keeper, to try to extricate me from the mess. I’m aware of my vulnerability in coming to Iran, a police state where hating America is the official policy, and where the U.S. still has no diplomatic representation. Have problems here as an American, and you’re entirely unprotected.

We slip past the embassy grounds, the driver not wanting to stop. We pass a government slogan painted on a wall that calls the U.S. “the most hated state before our nation.” And farther down, in bold letters: “We will make America face a severe defeat.” And now the embassy, itself, which is an unattractive place. A nondescript brick building, surrounded by an unkempt yard. An iron fence. An old eagle seal chipped away over the years but still visible on the front gate. It’s home to a Revolutionary Guard headquarters now and is known as “The U.S. Den of Espionage”—ludicrous and surreal-sounding, like something out of a Pynchon novel. It’s here where a reported 52,000 Iranians have voluntarily signed up for “martyrdom missions” against U.S. and British interests around the world, merely awaiting an order for mobilization.

Seeing the embassy and thinking of its history, I wonder what really lies in Iranians’ hearts. And in my own. I’ve come to travel Iran as a foreigner and a woman, much like my inspiration, the 1930s-era writer and explorer Freya Stark, and as I move from Tehran into the remotest corners of the country, my goal is to keep an open mind. Still, it takes a small feat of equanimity for me to see this place, to read these slogans, without shuddering in disappointment.

The photographer with me, Bobby Model, cracks the car window and sticks his telephoto lens outside. The driver, nervous about this transgression, picks up speed. We pass the famous murals painted beside the embassy gates: the Statue of Liberty with a skull’s face; the American flag in the shape of a gun. Bobby asks the driver to slow down, his camera on auto-focus and shooting away while I stay on the lookout.

A uniformed policeman takes notice of our creeping van, starts to walk steadily toward us.

“Someone’s coming!” I say to Bobby.

He snaps back from the window, hides his camera. Our van speeds away around the block. After a few moments, we look over our shoulders: no one.

Our guide is shaking his head. “Why do Americans always want to see the embassy?” he laments.

*

Here is where the Iranians go: Tehran’s Martyrs’ Museum. It’s just around the corner from the embassy and commemorates the estimated 750,000 Iranians who died during the ten-year Iran-Iraq War, as well as the reported 60,000 killed during the Islamic Revolution of 1978-79 which overthrew the former shah and his secular state. The human death toll from the war was staggering, and it didn’t even address those hundreds of thousands who survived with missing limbs, infirmities, insanity. Saddam Hussein started the war in 1980 by invading an Iran crippled militarily from its recent revolution. And with Iran’s Islamic fundamentalist regime being fervently anti-American, the U.S. government made the unsavory decision to assist him. As a result, Iranian mullahs—those religious leaders largely responsible for spreading anti-American sentiment—blame both Saddam Hussein and the U.S. for the deaths of Iran’s 750,000 sons.

On the walls of the museum, I see many of the dead pictured. In Iran they’re always called “martyrs,” to remind people of their unique sacrifice in the name of Islam—and of the bountiful rewards their spirits are supposedly enjoying in Paradise.

Among the exhibits: a black-and-white photo of an Iranian boy, perhaps nine years old, a member of a unit called the Basijis (composed mostly of young children and the elderly who were used, among other things, as human minesweepers), “martyred” by blowing himself up with a grenade beneath an Iraqi tank. Also on display: the original noose used by the shah’s men to hang an Islamic revolutionary; bloody, bullet-riddled clothes; paperwork from SAVAK—the former shah’s secret police network responsible for the torture, and deaths of untold numbers of Iranians. Photos of these unfortunates are pasted onto official forms, each individual reduced to a serial number. The reports, so meticulously kept, look like those made for the victims of Pol Pot and Hitler. The expressions of the doomed are the same: terrified, helpless, with those desperately entreating eyes.

A lone man looks the bloody uniforms and SAVAK papers, clutching himself and sobbing. The bloodshed still traumatizes the country. Painted on the sides of buildings, flashed and reflashed across television screens endlessly, are the faces of the dead. So that no one will forget.

*

Writers like to say that it’s impossible for Westerners to understand Iran. I can believe it, looking at a full-page story in the Tehran Times, “Iran’s Leading International Daily” newspaper, announcing that the Holocaust never happened. That the concentration camps and gas chambers never existed. I try to imagine the equivalent back home: an entire page in the New York Times devoted to the idea that several million people were never slaughtered.

The real question is: How many Iranians actually believe this? It’s impossible to know.

I walk around Tehran. Everywhere: the rising of steel girders, the mortaring of brick. Teams of laborers work ceaselessly in the hot desert sun, building high-rises for the rich in the shadow of nearby 18,606-foot Mt. Damavand, while cheap apartments for the poor reach further into the southern wastelands. This feverish city is fueled by expediency and profit, feeding on a materialism that smacks of the forbidden West. Levi’s and Samsung phones. Peugot cars. Madonna CDs. Any conceivable thing you could find in the land of the Great Satan exists here, imported from other countries. The finest titanium crossbows. The newest, most expensive digital cameras. Even pornography buffs stay up to date with the latest, raunchiest titles. Tehran, punished with economic sanctions in 1995 by President Clinton, still gets anything it wants.

The latest prize is enriched uranium. I’ve arrived in Tehran at a time when the U.N. Nations Security Council is attempting to entice Iran with economic incentives to discontinue its nuclear program. The country’s conservative, hard-line president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a blacksmith’s son who later helped orchestrate the 1979 U.S. Embassy take-over, has argued that uranium enrichment is only meant to serve civilian energy needs. Yet many experts, such as former UN Chief Weapons Inspector Hans Blix, believe it’s a cover for the secret production of nuclear weapons; the U.S. government agrees, viewing Ahmadinejad and his fundamentalist regime as a major threat to world peace. The Iranian president does little to dispute the image; he openly funds terrorist groups like Hezbollah, repeatedly calls the Holocaust a “myth,” and wants Israel “wiped off the map.” If nothing is done, experts estimate that Iran will have nuclear weapons in anywhere from three to seven years.

I walk through Imam Khomeini Square, named after the man himself, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, whose fierce, omnipresent stare defines modern Iran. He was the country’s first Supreme Leader, who died in 1989, a man who brought about the collapse of the iron-fisted dictatorship of the former shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and effectively ended 2,500 years of Persian monarchy. Khomeini replaced it with the world’s first fundamentalist Shiite Muslim regime, based on official interpretations of the Koran. Pictured beside Khomeini’s ferocity, his gravitas, one often sees the incongruously dazed, bespectacled face of his successor Ayatollah Sayyid Ali Khamenei. An autocrat, this bemused-looking figure wields absolute and often brutal control over all aspects of Iranian government and society.

Khamenei and his hard-line colleagues are the reason why all the women I see, including foreigners and non-Muslims like myself, are required by law to wear hejab,or Muslim women’s attire, over their normal clothes. Hejab consists of either a chador—a long, baggy black cloak that covers the entire body except for the face and hands—or a dark-colored manteau, a kind of long trench coat worn with a maghnaeh, or headscarf. Teams of the infamous “morality police” patrol the streets of Tehran in search of straying hair or exposed ankles, but they have their work cut out for them these days. Most women I see do their utmost to shirk the laws. They wear skin-tight manteaux in bright colors that stop mid-thigh. They show painted toenails and bare necks. Right after the revolution, to reveal a few strands of hair might have resulted in beatings or arrest, but some bangs are acceptable now. Still, expose more than an inch or two and you’re pushing it. Then you’re defeating the purpose of the headscarf, scoffing at Islamic modesty, and you could be seen as one of the silent, new-generation revolutionaries seduced by the corrupting tentacles of the West.

You could be someone like Farhnaz, say, whom I meet in a coffeehouse. She wears a tight manteau and a bright blue headscarf revealing bleached-blond hair. “I think we should gradually do without hejab,” she says. “It shouldn’t be a law. It should be a woman’s choice.”

An older woman, Batu, disagrees. She wears a full-length black chador, not a single hair revealed. “It’s the duty of a Muslim woman to cover herself,” she says. “It’s taboo for me to be seen by strangers.”

“Why is that?” I ask.

She thinks about it for a moment. “Tradition,” she says finally. “I’d be a bad Muslim woman.”

The headscarf in Iran has become both a symbol of religious piety and a benchmark of an individual’s political ideology. How a person wears it, what color it is, how much it exposes or covers, tells you much about what this person thinks about the current government and its policies.

Such varying opinions might have something to do with the fact that about 70 percent of the Iranian population is under 30. Most in this new generation have no direct experience of revolution or war, or the fear of SAVAK agents knocking on their door. Many grew up with satellite dishes, watching American TV shows such as “Sex and the City,” and they largely make up the estimated 15 million Iranians who now use the World Wide Web. Looking forward instead of back, they have turned Tehran into a dynamic, cosmopolitan city, with coffeehouses and art studios, vegan restaurants and shopping malls. Yet some things are still conspicuously absent: bars and night clubs. It’s illegal to sell or drink alcohol, to dance, to listen to most Western music. Such forbidden fruit have been pushed underground, surfacing regularly at secret parties. In Iran, one thing is clear: public and private Iran are two vastly different universes. You never know what a woman is wearing beneath her chador.

*

After a few days in Tehran, Bobby and I travel by Land Cruiser through a landscape untouched and vast, following the old Silk Road in the western part of the country. We have been assigned a guide and official minder, Abbas, as we would never be allowed to negotiate this part of the country alone. He is a short, burly man in his mid-40s, a self-described climber and photojournalist. Mysteriously, he often succumbs to dramatic spells of anxiety and moodiness, and we never know if we’ll be traveling with Dr. Jeckyll or Mr. Hyde.

How strange to be in far western Iran, in Lorestan Province, where the distant, thrumming city feels like a sinful dream. Nearly a hundred miles from the Iraq border, we greet a land where people still cut fields of wheat with scythes, reside in adobe-brick homes, and travel largely by donkey. Here live most of Iran’s ultra-conservatives and poor, people who existed by a medieval system of feudalism until the shah’s Land Reform of the 1960s, and who now share only a fraction of urban Iran’s wealth. It was from places like this, among these needy and uneducated, that Khomeini’s Islamic Revolution was birthed in 1978. To them, he is still the Messiah.

All around us, the Zagros Mountains erupt from grassy hills, twisted layers of limestone, granite, and shale shooting thousands of feet vertically. It would be a geologist’s or rock climber’s paradise, if only one didn’t have to deal with the pesky secret police, those grim men with walkie-talkies who track our whereabouts by day and make sure our passports are delivered at night. As a result, we’re wedded to an official “Itinerary” that must be approved by and filed with the police each day, and which all but excludes spontaneity.

We reach a barren, grassy hill, overlooking the Saidmarreh River, one of Lorestan’s main waterways. The silence and emptiness is confounding. No one. Nothing. Just these windswept hills. In the 13th century the Mongols tore through this country, razing villages and massacring all living things, and the landscape still looks devoid of any human presence. A local man, whom we paid to guide us for the day, points guiltily to a hillside pockmarked with holes: the site of a looted Bronze Age grave site.

There are scores of them in this region, a place that was unmapped and unexplored well into the 20th century due to the ferocity of local tribes who had a reputation for killing any outsiders they encountered. Still, one unlikely Western explorer managed to gain special access: a diminutive British woman named Freya Stark. I have long admired her tenacity; she is the inspiration to reach outside the cities into remotest Iran. Always traveling alone and unarmed, wearing outrageous hats to hide a childhood disfigurement, Stark had an obsession with riding blithely into some of the country’s most dangerous regions. “I may confess,” she wrote, “that I had never thought of why I came [to Lorestan], far less of why I came alone. I traveled single-mindedly for fun.” She was the first Westerner to map large regions of Iran, using her gender to trick officials: “The great and almost only comfort about being a woman,” she mused, “is that one can always pretend to be more stupid than one is and no one is surprised.” She would go on to write about her travels in this region in the 1934 classic, The Valleys of the Assassins, while her mapping and exploratory achievements would earn her a prestigious award from England’s Royal Geographical Society and, later, a knighting by the Queen of England.

Stark risked her life to journey to this part of Lorestan, searching for a Bronze Age hidden treasure that was rumored to be stashed among these hills, but she never found it, leaving behind a lingering mystery. There was one canyon in particular that was difficult and dangerous for her to reach—the “Unbeliever’s Defile” or Infidel Canyon—which she thought might contain the treasure. As she didn’t complete her search, I want to find the canyon and look for myself. Using 60-year-old Soviet military maps and information from Stark’s book, I narrow down the location to a remote, largely uninhabited region several miles long between the Rua and Saidmarreh Rivers. My search is complicated, however, by a lack of bridges and roads, and by villagers who can’t provide me with reliable information.

After a long day of searching: a breakthrough. We come upon a local man, Majik, who says he knows where the canyon is. Furthermore, he’ll take us there. We drive off-road up a mountainside, past fields of mature wheat that gleam in the late afternoon light. Far below, the narrow Rua slices through sandy, desolate bottomlands before winding into a tiny cleft between gigantic cliffs: Infidel Canyon. Excited, we descend the other side of the mountain and park our vehicle. We follow Majik to the mouth of the canyon, the Rua emerging from between sheer cliffs. Before us is a kind of Eden: blooming pomegranate trees, pink-flowered eucalyptus, clear water gurgling over stones. To continue, we must remove our shoes and wade through the stream. I begin to roll up my pants legs like the others, only to see Majik staring at my bared shins. I haven’t been wearing my hejab long enough to get used to the idea that only face and hands may be exposed to the outside world. I pull my pants legs down, put my socks back on, and follow the others fully clothed. Now I find that my chador drags in the water and catches on my legs. Wearing it over my normal clothes, in the hot desert sun, is already giving me painful heat headaches. It occurs to me that a woman would have a hard time doing any hard-core outdoor activity in hejab—which is, perhaps, the point.

We stop about halfway up the canyon, ancient pottery shards lying like detritus in the water. Majik points to a ledge high above us where we can see visible ruins—and, perhaps, graves. We scan the cliff to figure out a way up, realizing that we’ll have to do some serious rock-climbing, without ropes. The men begin to climb carefully and slowly, with me following last so no one will have to look up my chador. But it’s dangerous business being modest: the headscarf keeps falling in front of my eyes, blocking my view, and my legs can’t reach out properly. I climb back down, unable to continue in such clothing. Instead, I tuck the ends of the chador into the top of my pants and replace the headscarf with a bandanna. Majik will just have to deal with it.

We reach the upper ledge, barely half a foot wide, that runs along the cliff face. That ancient men decided on such a precarious location for their fortification speaks of the high risk of attack. It’s hard enough to travel it slowly in the daylight. I search for handholds, sliding along belly-to-stone along the ledge. But we’re rewarded for our perseverance: a sizeable stone building overlooking the canyon. Inside is what appears to be a large burial chamber, already opened and looted.

Beyond the ruins, the ledge ends. I wonder if Stark’s treasure is hidden elsewhere on this cliff face, in a nook or on a distant crag. It’d take another expedition, with adequate climbing equipment, to properly search the chasm’s entire length. But anyone interested will have to hurry. Majik tells us that this idyllic canyon will be gone in a year’s time. The government is nearing completion of a large dam on the Saidmarreh River that will put most of these ancient cemeteries and ruins underwater forever. Stark was the first Westerner to explore Infidel Canyon, and, sadly, it looks as if Bobby and I will probably be the last.

*

In the rugged lands around Infidel Canyon live the Lurs, a traditionally nomadic tribe scattered across the isolated valleys and high passes pf the Zagros Mountains. For much of her exploration, Stark enlisted their help, though they were known historically for their “extreme hostility.” To date, only a handful of Westerners have witnessed their culture, and no Western magazine has ever documented them. I want to visit some, though I’m told this could be dangerous: they’ve started carrying transistor radios, are becoming negatively influenced by anti-American propaganda broadcast by Iranian mullahs.

“If we meet Lurs,” Abbas suggests, “tell them you’re Canadian.” It seems a sorry state of affairs that I must go around lying to people at first meeting.

But Abbas finds us a group high in the mountains, who supposedly don’t have radios. Who will be able to welcome us as friends. We arrive at the black goat-hair tents of a Lur family who come out to greet us. The matron is Shanoz, 45, who flashes a warm, artless smile and a youthful radiance that belies her age and heavy responsibilities. Here, at nearly 8,000 feet, in all manner of extreme weather, she and her family must be self-sufficient, depending exclusively on their animals for sustenance. She wears a traditional Lur turban around her head, her hair and neck showing. It’s perhaps the only place in Iran where I can shed the hejab, as the family has no qualms about my walking around outside—as their women do—in shirt and pants. In the high peaks of the Zagros Mountains, practicality and sensibility win out.

When she asks my nationality, I ignore Abbas’s advice and reply honestly, in Persian, that I’m American. But she doesn’t seem fazed.

“How long does it take you to drive your car to Lorestan from America?” she asks me.

Her daughter, Zeba, 16, joins us. The usual marriage age among these Lurs is 15, so Zeba is already married. So is her older sister, Fatome, 20, whose husband, with his blue eyes, fair complexion, and light-brown hair, could be of Kurdish descent. He gazes at me and Bobby with a proud, fierce detachment. Though we’ve gotten permission to take photos, he still challenges Bobby’s camera with a belligerent stare.

The family lets me help with the goat milking. But it’s an acquired skill, knowing how to grip and squeeze the bloated teats, and I make a mess of it. The milk goes in a goatskin bag, along with some salt, which the women then vigorously shake until the contents separate into dukh, sour milk, and butter, which the family smears lavishly on tortilla-like flat bread called saj. Their daily diet: whole milk, yogurt, butter, cheese. I cringe for their arteries, yet everyone looks thin and robust. Atkins Diet in the extreme.

While Bobby and Abbas walk around shooting photos, Shanoz welcomes me into the tent where Fatome and her husband rest. They have a baby, whom Fatome rocks in a hammock in the corner. I ask if I can take over, and I swing the child back and forth, making funny faces. The baby fills the tent with her laughter, and I find myself intoxicated with the sound. In her smile, I discover, is something wholly beautiful and ineffable.

I hear some Persian—fuzzy-sounding, full of static—and turn to see Fatome bringing out a radio and delivering it to her husband. He fumbles with it for a moment until he gets some kind of news broadcast and listens intently, occasionally readjusting the antenna. I wonder what they’re being told. Why they listen so closely. The whole family leans toward the voice, and the baby looks soberly at me, for I’ve forgotten to swing her and make my silly faces.

After a time, Fatome’s husband turns off the radio. He puts it back under a cover against the tent wall and glances at me with his fierce blue eyes, but I can’t read his expression. His other daughter, a toddler, wobbles by. All at once he grabs her and gives her a sloppy kiss on the cheek. When he looks my way, he’s smiling at me, his eyes dancing.

*

Long before al Qaeda or Hezbollah, there were the Assassins. The word comes from hashishiyyin, or “eater of hashish,” the name given to a heretical Muslim sect known as the Ismailis that split from its Shiite brethren at the end of the 11th century and found a home in the dry, harsh valleys of Iran’s Elburz Mountains, in northern-western Iran. According to legend, their founder Hasan-e-Sabbah, drugged naïve young men and had them awake in his sumptuous palace gardens. Astounded, convinced that they had awoken in Paradise, the men quickly committed to Hasan’s every cause. They participated in the first organized terrorism in recorded history, so thoroughly mastering the art of ambush and assassination that they terrified the surrounding countryside for nearly 200 years. Hasan established some 60 castles, choosing only the most remote, inaccessible sites on top of buttes or cliffs. His best known was Alamut, “Eagle’s Nest,” resting on a treacherously high spit of rock. It held his main headquarters and palace until the Mongols decided they’d had enough of the Assassins. It took three years of sieges, but they finally conquered Alamut and the other castles, successfully ending the Ismaili kingdom in Iran, Mongol-style, with plenty of severed heads.

Stark visited Alamut in 1930. Even then, it was a burgeoning tourist attraction for Westerners, made all the more so by her important discovery of nearby Lamiasar Castle, another of the Assassins’ strongholds. But then there is Nevisar Castle, built at an elevation of over 9,000 feet in a rough, uninhabited stretch of mountains to the east of Alamut Valley. Tourists don’t go there. In fact, virtually no one does as there aren’t roads or easy access. Stark described in her book an arduous climbing adventure to get there—one I’d like to repeat.

Abbas is already having one of his bad days when I tell him that Bobby and I would like to climb to Nevisar Castle. This news leaves him tight-faced and piqued, as visiting the castle will require an unwelcome change to the Itinerary, with all its accompanying faxes and phone calls to the police. He tries hard to dissuade us by telling us that the only trail to Nevisar is wiped out due to a landslide, but we find a man who knows an alternate route. It’s settled.

We leave first thing the next morning. I soak my hejab and underlying clothes in an attempt to keep cool, tucking the bottom of my chador into my pants. My altimeter reads over 7,000 feet as we climb some steep slopes covered with pink and yellow wildflowers. The roar of a waterfall competes with the bleating of shepherds’ flocks, but the landscape is otherwise empty and vast, the sky, cloudless. When we run into a lone shepherd tent, I yank down the bottom of my chador and pull up my headscarf. Already, the heat is oppressive, and white salt trails run down the front of my chador. At last we reach the top of a saddleback at over 8,000 feet, where Abbas says we’re stopping.

“Where’s the castle?” I ask.

He points across a valley, to the mountains opposite us.

“So we’re not there yet,” I say.

Mr. Hyde appears. Abbas’s expression hardens in inexplicable anger. He says we’ve done our climbing for the day, that it’s enough for us to gaze on the mountains which contain the ruins of Nevisar. Bobby and I glance at each other, perplexed. We thought all the necessary calls and faxes had been made for changing the Itinerary. We thought we’d all agreed to reach the castle. I begin to suspect that Abbas just isn’t in the mood for any more exercise today. Regardless, we’re not at our castle yet, and now the biggest impediment to our getting there isn’t the rugged terrain or heat or elevation, but our guide’s bizarre wrath. I begin to envy Stark, who had only a few brigands to attend with.

Determined, I strip off my black chador and headscarf and tie a bandanna around my head, as I’m not expecting to run into anyone in the desolation before us. In forbidden pants and T-shirt, I head down the opposite side of the saddleback with Bobby, Abbas reluctantly following behind. We soon reach the valley, and I begin ascending the nearest ridge. The climbing is steep and exhausting, but at the top of the 9,300-foot-high ridgeline I’m rewarded with a sight of the misty expanse of Alamut Valley, enclosed by two mountain ranges. I hike along the narrow spine until it ends at a precipice. Ahead is a small butte covered in ruins: Nevisar Castle. I’ve nearly made it.

Obviously the Assassins had their work cut out for them just reaching this place—let alone building a fortification here. Bobby and I sit on the peak, looking through binoculars and discussing possible ascent routes to the castle. Abbas insists we can’t get up without ropes, though both Stark and another explorer, Peter Willey, apparently made it unaided. To punctuate his displeasure with us, he starts making cell phone calls, loudly complaining about us in Persian. Bobby and I consider our options. The real problem is not the climbing, it’s that the sun is already low, and we have no camping gear and very little water. There seems to be no choice. We’ll have to give up here to return to the village by dark. When Abbas hears this news, he abandons us immediately, making his own way down the mountain. We watch him go, grateful for the silence, admitting to passing fantasies of pushing him and his cell phone off the mountaintop.

*

We trade in the brown, dry mountains of Alamut Valley around Nevisar Castle for the verdant peaks near the Caspian Sea. We’ve also swapped a truck for a mule train, riding horseback across ancient Salambar Pass at 10,400 feet. We follow a trail that winds past roaring glacial streams and through meadows teeming with wildflowers. We’ve found a blithe country, flush with deciduous trees and rich grasses that tempt our mules to loiter, wild rosebushes sending up a fragrance that travels with us on the breeze. Stark followed these same trails by mule, at nearly the same time of the year, to our same destination: the hot springs of Ab-i-Garm.

They’re found on the eastern side of the roaring Chierakh River, housed in a recessed cave, reached after several hours of hiking at over 8,000 feet. Though remote, they’re obviously a popular destination for Tehran’s climbing clubs, and the area is overrun with tents. Scores of male hikers gape at me. One man finds my presence so strange that he must record the moment for posterity on his camcorder. How strange to be the only woman in such a place, bundled in hejab, while men run around freely in shorts and T-shirts.

Crossing the river is not for the faint of heart. You have to swim through ice-cold whitewater up to your neck to get to the other side, holding onto a rope so the current won’t sweep you down the mountainside. Our muleteer throws a stone into the river to test the depth, deciding that the mules can carry us across. This seems dubious to me, but I leap on our trusty gray. With no stirrups, I lock my legs around its belly and grab its stubby mane. I’m barely stabilized before it ignores our chosen crossing route and heads toward the worst of the rapids—and what seems like certain death. Desperate, I yank on the halter and order it to stop.

Mules, I’ve learned, have a limit to how much human authority they’ll tolerate. In this case, the animal doesn’t give a damn what I say. Water surges past us. Its hooves slip on hidden rocks, and I feel its muscles harden against the swift current. I keep waiting for it to stumble, to lose its footing and send us cascading down the mountainside. But it is an animal of steel. Wholly unperturbed by the crossing, it plows straight ahead, over boulders, through violent whirlpools, until it leaps casually up the opposite bank and comes to a halt. I slip off its back, light-footed from adrenaline. Iranian men stand nearby in their underwear, having just completed the crossing, and stare unabashedly at me.

The others cross successfully by mule, and we camp on a small hill overlooking the campers. I stare longingly at the hot springs, a small pool resting in the cliff face, not knowing when I’ll be able to go in. Men and women cannot swim together in Iran. If I decide to even stick my toes in the pool, guards must be posted 50 feet away to fend off any approaching men and protect my modesty. I decide on a plan with Bobby: later, under the cover of darkness when most of the campers will be asleep, we’ll sneak down to the hot springs and take a forbidden coed dip.

We don’t have to wait long after dark before most of the tent lights turn off: with no women or alcohol, there’s little incentive for the all-male crowd to stay up late. As 10p.m. approaches, Bobby and I leave our respective tents and grab our headlamps, slipping into the night like errant teenagers. We rush past one tent after the next until we reach the pool, and Bobby goes inside to see if anyone’s there. He quickly returns.

“Three dudes in tighty-whities,” he reports.

“Damn,” I say.

We wait in the shadows of the mountain until the men finish up and leave. At last, we dash in, having the hot springs to ourselves. The pool smells strongly of sulfur, stalactites hanging from the ceiling. It’s a bizarre, cozy little place, the water refreshingly warm. I can see why Stark hung out here for an entire day. We enjoy a long soak and then sneak back into the night. As we slip by the sole lit tent in the camp, a man pokes his head out and sees us.

“Salaam!” He waves. “Hello!”

I quickly cover my head with the hood of my chador, but it’s more than evident that the two of us, wet and dripping, just came from the hot springs together. The man, named Kamrun, invites us inside, and though I’m naked under my chador, I decide to chance it. Bobby slips in the tent first. It is, it turns out, a very small tent stuffed with seven middle-aged Iranian men. In the center is a lit propane tank, its giant flame threatening to incinerate us all. I pause at the doorway, the men gaping at me in disbelief. When I wave to them, they forget, momentarily, to respond. Bobby takes a corner seat, and I squeeze in between him and Kamrun. It occurs to me that I must be committing my second sin of the evening: fraternizing after dark with strange men in a very small tent.

Kamrun is the youngest of the group, probably in his late 30s and the owner of a pizza shop, and he showers us with pistachios and hard candies. His English is about as bad as my Persian, but we crudely communicate.

“Shohar?” he says, pointing to Bobby. Then he remembers the word in English: “Husband?”

I consider his question as dates and tea are passed to us. Bobby, who only smokes when he’s nervous, now accepts a cigarette.

“’Husband’?” I say to Bobby. “What is ‘husband’?”

“’Husband’?” Bobby says with pretend puzzlement.

We shrug. Kamrun lets it go and offers us wafers. We’re fed like kings, and just when I think the hospitality can get no better, a grinning man named Mustafa pulls out his pièce de résistance: a large bottle of Armenian vodka.

“My, my, my,” I say.

Mustafa extracts lemons and sugar from his bag and prepares what is to be my third sin of the evening. No wonder the inhabitants of this tent are up at an ungodly, carnal hour.

But our tent is a microcosm of larger Iran, and so, of course, there are the Dissenters: a man in a red shirt, sitting across from me, and his bespectacled friend. Both take umbrage at the appearance of the illegal alcohol, and Red Shirt seizes the bottle and begins to pour out its contents over a tin of cinders. This creates a major fire hazard until Mustafa, unperturbed—as if he regularly must rescue his vodka from the hands of wrongdoers—seizes back the bottle and continues his mixing of the fixings.

Bobby receives the first glass. He takes a sip and offers it to me, the Dissenters eyeing me disapprovingly. Drink from this glass, I see, and I will lose whatever remains of my feminine virtue.

“Oh, what the hell,” I say.

I drink. It tastes like lemon-flavored turpentine, is some vile moonshine. I give Mustafa back the glass. Bobby, not normally much of a drinker, sits back and assumes a cool, calm air, as if he has spent all his life smoking and drinking with Iranian men crowded into small tents.

“Dam-it garm!—May your breath be warm!” Mustafa declares, raising his glass. All the drinkers in the tent chime in and hit their glasses together. This becomes our phrase of solidarity. Whenever one of the Dissenters begins to protest, we all raise our voice in one great cheer to the Universe: “Dam-it garm!”

Several drinks later, the bottle of vodka is seriously depleted. Red Shirt has made two more attempts to dump its contents on the cinders, and the tension in the tent remains high. I figure it’s about time we leave, and Bobby agrees. We put down our glasses, thank our hosts, and extract ourselves from the tent.

As we retreat into the darkness, Mustafa and Kamrun yell out their plea of “Dam-it garm!” to a universe erupting with stars.

*

We return to Tehran. It’s time now to say goodbye to Abbas, who hates us, and to try our hand with a new guide, a Mr. Soufi, for the remaining days of our trip.

And how to describe Mr. Soufi? Such infectious exuberance. Such enthusiasm and joy. I have never in my life met anyone like him. He lived in the U.K. for six years, mastered English, and now his brain, full to the brim with arcane Western knowledge, seeks constant release. On the plane ride from Tehran to Shiraz, we discuss Lacan and Jung, quantum mechanics, the Gospel of Thomas. It’s a torrent of theorizing, questioning, conjecturing that continues en route to the hotel and picks up the next morning on the way to the ancient ruins of Persepolis.

One imagines, talking with Mr. Soufi, that everything can be, ultimately, understood. I want him to explain Iran. The contradictions. Why, for example, fervent anti-American mullahs send their children to U.S. Ivy League schools. But we arrive at Persepolis, and Mr. Soufi can barely contain himself. Here, he tells me, was the spectacular capital of Darius the Great, dating from 520 B.C. A generation before, Darius’s father-in-law, Cyrus the Great, founded the Persian Empire—the largest kingdom the world had ever known, spanning from Libya to China. It survived until 330B.C., when Alexander the Great conquered it and burnt Persepolis to the ground. Now, 2,500 years later, little remains for the imagination, but Mr. Soufi is not dismayed.

We walk through the Gate of All Nations, which is flanked by gigantic sculptures of winged, bearded men with the bodies of bulls. Old Western travelers cut their initials into the stone, the earliest signature dating from 1522. In the center of Persepolis is a well-preserved staircase, leading to the former palace, that is decorated with carvings of the different peoples conquered and assimilated into the empire. Aryans, Babylonians, Phoenicians, Ethiopians. Each man carries something unique to his homeland, as a tribute to Darius the Great, King of Kings, believed by the ancient Zoroastrians to be God’s chosen ruler of the earth.

Mr. Soufi pulls me aside, out of earshot of the other tourists, and points to a statue of a bull. When he speaks to me, it is in a whisper. “I was here at this spot for a week. Morning and night I came. I nearly slept here.” He points excitedly at the bull. “Look at it!”

I look. The bull has ornate spirals for nostrils, bold eyes, a strong brow. “Yes?” I say.

“I watched it in all types of light,” Mr. Soufi whispers. “Morning. Evening.” Tourists come near, and he ushers me quickly out of their range of hearing. “Look at the bull!” he says, gesturing emphatically. “Look at it! Do you know what I discovered?”

I look closely. I shake my head.

Mr. Soufi’s face erupts into unbridled excitement. But Bobby is approaching now. “Come. It’s not for others to hear,” he says, ushering me further away. We stand at a safe distance from everyone, but Mr. Soufi takes one more look over his shoulder just to be sure. At last, he turns to face me. I am ready to hear his answer to the great, enigmatic bull—to Persepolis—perhaps even to life itself. Yes, here will be the meaning I’ve sought. Iran. The West. The answer to all of it, to everything, and I can go home.

“Do you want to know the answer?” Mr. Soufi asks. He takes another quick glance over his shoulder.

“Yes,” I say. I realize I’m also whispering. Am looking over my shoulder, too.

He points to the bull. Beckons me close to him so he can whisper into my ear: “Conceit!”

*

Perhaps the most liberal place in all of Iran is Shiraz. The city of poets. Hafiz, a Sufi and one of the world’s greatest Persian poets, lived and died here in the 14th century. He is beloved in the East and West alike, and it has been said that more copies of Hafiz’s poetry have been sold in Iran than copies of the Koran. As Hafiz is one of my favorite poets, I make a pilgrimage to his tomb.

His grave rests in the midst of a fragrant park, full of rosebushes and birdsong. Soothsayers stand at the entranceway with boxes of fortunes containing lines from Hafiz’s poetry, their parakeets pulling out fortunes with their beaks. We enter the park and walk toward the blue-tile cupola of the gravesite. Immediately, I see that there’s something different about this place. Unmarried couples stroll—illegally—hand-in-hand. Young lovers lay beside each other on blankets. Women wear short, tight manteaux and see-through headscarves. Here are Sufi dervishes in white, looking like Jesus with their beards and long hair. Western hippies with dreadlocks. Arab women covered in black burkas, their eyes greeting the world through tiny slits. Everywhere: Easterner and Westerner, young and old, liberal and conservative, Sunni and Shiite. All gathered in the park around Hafiz’s tomb to pay homage to the man who spoke of the universality of love.

Mr. Soufi is inspired to song. He sings Hafiz’s poetry aloud to passersby, who receive his joy with hesitant, fearful eyes. I open my book of Hafiz randomly, to receive my own oracle:

I understand the wounds that have not healed in you.

They exist because God and love have yet to become real enough

To allow you to forgive the dream.

I place my fingers on Hafiz’s polished marble grave. An old dervish sits nearby, watching. He tells me he is 83, has practiced Sufism, a mystical off-shoot of Islam, for over 60 years. He offers me a yogurt ball to suck on, and we sit together, watching the crowds. I want to ask him about what Hafiz said. About forgiving the dream.

“Our government is awful,” he muses. “All the problems we have in the world now are caused by religion, because there are people who believe that their religion is better than others’. I don’t care about a person’s religion—I care that he or she is created by God.”

*

I stand in the Jameh, or Friday Mosque, in Isfahan, among dim, empty corridors first built in the 11th century. A man named Majid is talking to me; he sought me out when he heard I was an American. He is 43 now, wants me to know that he fought in the Iran-Iraq War for four years, breathed in Saddam’s poison gas, and is now crippled for life. He wants to give me a history lesson about this mosque and about Isfahan itself, one of Iran’s holiest cities. How the Mongols attacked first, followed by the Ottoman Turks, then the Afghans. Spilled Iranian blood has stained the floors of this mosque several times over. Did I know that? So much blood.

I am waiting for his point. Which comes finally, circuitously. How Western countries have a history of invading and exploiting Iran. How the U.S. would like to do the same and is starting wars against Muslim people around the world. How Iranians, at any cost, must resist the U.S. and develop their nuclear program.

“What do you see as America’s greatest threat to your country?” I ask him.

He doesn’t need to think about it. “America’s poor morality,” he says immediately.

Not bombs. Not planes flying into buildings. Morality.

“We don’t want to be like you in the West,” Majid insists.

We say goodbye. Mr. Soufi badly wants to show me the Imam Mosque, built in 1628, Iran’s equivalent of Notre Dame, but I’m not really in the mood to see it anymore. Something to do with my talk with Majid. With some point that occurred to me but was immediately lost.

But we go to the mosque anyway. Mr. Soufi has me walk inside, close my eyes, and then open them to the sight of the dome. Above me rises a whirl of ornate turquoise-colored tiles tapering to a gleaming yellow apex that is struck by a single ray of sunlight. It’s an exotic beauty unlike anything I’ve seen. Beauty neither of the East nor West—something uniquely and purely Iranian.

“If you have any ideas, I’d like to know,” Mr. Soufi says, pointing at the dome. He has studied it incessantly, has his theories. He waits a moment, but once again the frenetic, insatiable workings of his mind can no longer be contained. His world has become a cacophony of dizzying symbols and signs. Do I know that the spiraling of the designs on the arabesque tiles along the length of the room mathematically equals the wavelength of sound at 33 hertz? That this expresses the law of the alternation of sound? That this matches exactly the human heartbeat?

He is utterly, unabashedly transfixed. “Look at it!” he insists. “Look!” The arabesque motif. The curves of its leaves, its stems. The secret pulsing of life itself.

His voice echoes off the dome, and some Iranian tourists stare at him in curiosity and alarm. I exit the labyrinth of Mr. Soufi’s world, come up for air in my own. Sparrows fly round the top of the dome and, watching them, I remember what Majid told me in the Friday Mosque: “We don’t want to be like you.” And what I failed to say to him, and should have, was that we already were one and the same. In each other, we saw only the shadows of ourselves. My “immorality” was really his unowned guilt. And his “intolerance” revealed only my own self-judgment.

“No one really knows anything,” I say to Mr. Soufi.

*

In a day, I’ll be returning to the U.S. The sun sets over Isfahan’s main square, and crowds of people take advantage of the gentle light and cool breezes. The tiled dome of Imam Mosque gleams in the departing light, and a great white horse with a kingly stride races round and round the square, pulling a black carriage.

I want to see it all better. Take it in. The best place for this, I’m told, is a little-known yet ancient coffeehouse just to the left above the entrance to the bazaar. I search for the place, find some narrow stairs that wind upward to it. At the top of them, just before the entranceway, is a posted sign in English: “For women, service is forbidden.”

I consider this. The manager watches me from a nearby desk, taking slow puffs from his water pipe. Over the coffeehouse’s patio, I see flocks of doves rising in the purple light. I shrug. I climb the last few stairs and enter the place, walking past his desk and taking a seat on a cushion on the patio. He follows me immediately, of course. He’s not happy. Not happy one bit. Starts to accost me in Persian.

Forgive the dream.

I turn my back to him and order some tea. Imam Square looks softened by the coming night, families sitting on blankets, children clutching balloons. There is the feel of a festival to the evening. Every night here, at just the right time, this communal peace.

The manager reappears, strides over to me, his face livid with rage. I am ready for a showdown, if that’s what it’ll take. But I see he’s carrying a tray: my tea. It’s the first time I have understood this country.

|

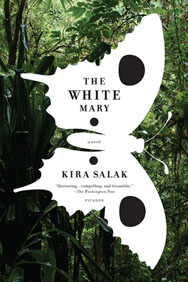

THE WHITE MARY

by Kira Salak

"A gripping debut novel."

Publishers Weekly Pick-of-the-Week

"There aren't many books that we hand to friends, urging,

'You have to read this.' The White Mary is one of them."

Cleveland Plain Dealer

"Riveting."

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

"With The White Mary, journalist Kira Salak makes a stunning

debut as a novelist. This is a story whose beauty and power

sweeps you along, like the jungle rivers that bear her heroine

into the heart of New Guinea in search of a vanished American."

--Philip Caputo

|

© 2008 Kira Salak, KiraSalak.com--all rights of reproduction in any form reserved

![]()