LIBYA: THE LAND OF CRUEL DEATHS

(published in National Geographic Adventure magazine;

Anthologized in The Best American Travel Writing 2006;

Winner of the Lowell Thomas Award for Foreign Reporting)

“You come, Madame,” the man says to me.

He wants to show me something—something “special.” And maybe it’s the sincere look in his eyes, the supplication, the knowing, but I follow this complete stranger across Tripoli’s Green Square and through the stone gate of the ancient medina, or historic Arab quarter. It’s my first night in Libya; I arrived only three hours ago in a country that’s still a mystery of culture shock and conjecture. So many people told me not to come here. Terrorist cells, they warned. Al-Qaeda. Don’t forget the Lockerbie bombing. And of course Muammar Qaddafi, global pariah, former patron of every rogue cause the world over. The U.S. State Department advises extreme caution.

It all gives me the shivers, like entering a house that’s supposedly haunted. I keep looking over my shoulder. Can people tell I’m American? My shoes, maybe? The brand of my jacket? Such paranoia.

Few are out tonight. It’s the eve of Eid al-Fitr, the three-day Muslim holiday that marks the end of the month-long fast of Ramadan. The store-keepers look at me curiously as I pass, and I touch my hair before their glances: most Libyan women wear headscarves and long coats to hide the shape of their bodies. Libyan men wear whatever they please—Western clothes, usually, though some prefer the traditional North African jelabia: baggy pants and a shirt reaching to the knees. An old woman passes, wrapped head to toe in a white garment, a burnus, held tightly over her face, a single eye peering out at me through the folds. Otherwise, the medina is mostly deserted, the small stores like lighted vestibules in the dark and cavernous depths of the Old City.

The man urges me down a dim passageway, but I pause at the edge of the shadows. Where are we going? I demand in French. What do you want to show me?

“Something special,” he insists, beckoning.

I sigh and follow. We enter the heart of the medina. Built over the ancient Roman town of Oea, its carved columns are still visible at the corners of buildings. Modernity has all but vanished here, and I trespass in a time when donkey carts shuddered by and slaves were driven down the narrow streets.

“Come, come,” the man urges.

We go deeper into the labyrinth. Great stone arches cross overhead, cutting shadows across the dank walkways. The scent of incense wafts down the corridors, our footsteps loud and impudent in the silence. The man stops. He enters a clothing store and sends away the young boy tending it. Stepping behind the front counter, he raises his eyebrows at me in conspiratorial confidence.

“Come,” he whispers.

I do. I step forward gingerly.

He looks out at the front of the store. At the aisles around him. No one. He slowly pulls out something small, balled in his fist. Eyes wide and intent on me, he shakes it out.

“Yes, Madame?” he asks. “You want to buy?”

I lean down to see what it is: a lace bra with matching thong panties.

*

It’s hard to know what’s real in Libya. I finger the Qaddafi T-shirts in a gift shop at the Roman ruins of Leptis Magna, outside of Tripoli. Qaddafi poses on them like a rock star, face hardened and puckered, eyes gazing majestically toward the clouds. He hangs in every building, in every city intersection, large and wide and belligerent over the streets. There aren’t billboards in Libya—there is Qaddafi.

His country used to be one of the poorest in Africa until, in 1959, Esso (now Exxon) discovered massive oil deposits beneath the sands. And not just a trickle—these were the largest petroleum reserves on the African continent. Western nations salivated at the prospect of buying cheap oil, and Libya soon became the richest nation on the continent.

Qaddafi, though, with his chameleon-like policy changes and about-face gestures towards the West, remained something of an enigma from the very moment he took up Libya’s reins in 1969. Only 24 years old, Qaddafi seized the oil-rich nation from its monarchy in a near bloodless coup. Then, in a country larger than Alaska with a population smaller than Connecticut’s, he began testing his “Third Universal Theory,” a self-created political philosophy that meshes, among other things, 19th-century French anarchist thought with the 1,400-year-old dictates of the Koran. A few years after taking power, Qaddafi went off into contemplative exile, returning with his manifesto, The Green Book (an allusion to Mao Zedong’s Little Red Book), which denounces capitalism and communism as variations on “slavery,” spurns all political parties as forms of “dictatorship,” and advocates direct rule by People’s Committees according to Islamic law.

To Qaddafi’s credit, most Libyans will tell you, he could have gone the way of the corrupt Idris monarchy preceding him and pocketed most of the oil funds for himself and his cronies. Instead, noticeably, life for Libyans dramatically improved. Qaddafi promised “a home for all Libyans” and, to the best of his ability, tried to deliver on that promise—at least in the beginning. Great modern cities and new residential areas rose from the dust of the Sahara. Entire populations living in ancient mud-brick caravan towns in the desert moved to modern dwellings with running water, electricity, and satellite TV. A country which had only decades before been suckling on the largess of international aid organizations now possessed the highest GDP in Africa. Libya had become a kind of latter-day utopia.

The store clerk asks my nationality, and I tell him the truth: American. I’ve been telling some people that I’m Canadian—seems safer, easier, in a country that has an “American Aggression” postage stamp series. But the man smiles broadly, enthusiastically. “American?” he repeats, as if to make sure he’s heard right. I nod. “Ah! You are welcome to Libya!”

I wish I could believe him. Not very long ago, Americans weren’t very welcome here. In 1981, with Qaddafi openly supporting nearly every revolutionary or Islamic extremist cause in the world—from the IRA to the Philippines’ Abu Sayyaf to the PLO—President Ronald Reagan declared Libya a state sponsor of terrorism and severed all diplomatic ties. Qaddafi was, by that time, doing everything possible to alienate himself from the West—and the U.S. in particular. He engaged in sparring matches with American naval forces in the Mediterranean and was implicated in the 1986 German disco bombing that killed 20, including two American soldiers. In retaliation Reagan bombed Libya’s two largest cities, Tripoli and Benghazi, which only upped the animosity between the two countries. Before long, Qaddafi was using his vast oil revenue to develop chemical and biological weapons programs in cohorts with China and North Korea, buying $20 billion in arms from the Soviet Union. And then in 1988 there was Lockerbie.

Call it the defining moment between U.S.-Libyan relations, and the event that would cement Libya’s pariah status throughout the West. Two men, believed to be Libyan secret agents, bombed Pan Am flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, sending 270 people to their death. It would take Qaddafi’s delivery of two Lockerbie suspects to the U.N.’s criminal tribunal in 1999, followed by his 2003 renouncement of weapons of mass destruction programs to put him on the course of reconciliation with the West. U.S. travel restrictions were finally removed in 2004, nearly five years after the EU lifted theirs—which explains why, of the hundreds of nationalities listed in the Leptis Magna guestbook, I come across only two Americans.

The last time Libya was so closed to the West was back in the early 1800s, when most Europeans entered the country as slaves captured by the notorious corsairs of North Africa. Lying at the heart of the dreaded Barbary Coast, Tripoli—known ignominiously as “Barbary” to many Europeans—acquired much of its wealth from attacking Christian ships and towns and carrying off the people to sell as slaves. For centuries, towns as far north as Ireland and as far south as Sicily had their entire populations shipped to the galleys and harems of North Africa, convincing terrified Europeans that anyone attempting to explore the Muslim Sahara could only meet with, as adventurer George Lyon put it, “a cruel death.”

Still, this ominous reputation didn’t stop Scotsman Hugh Clapperton, who, in 1824, became the first Westerner to fully explore inner Libya—known as the Fezzan—and reach the interior of Africa by crossing the Sahara. I have come to Libya, in part, to follow his trail, to see how he accomplished such a difficult feat. Clapperton is a hero of mine, one of those old-time explorers who was always sick with one serious illness or another (dysentery, malaria) in a time when drinking mercury or bleeding was one’s only medical recourse. Still, he plodded through the triple-digit heat of the bandit-ridden Sahara. His journals—the fullest, most unbiased account of early Libya—were lost for nearly two centuries. They were finally unearthed in a South African archive and published for the first time in 2000.

I carry Clapperton’s journals with me now as I head out to the ruins, a couple of “tourist policemen” eyeing me. Groups of more than two foreigners aren’t allowed to travel in Libya without the accompaniment of such government-assigned watchdogs. But as I’m traveling with only one other person, photographer Bobby Model, I escape most of this scrutiny. Still, we’re the official wards of a Libyan tour agency. While independent travel is certainly possible in Libya, the lack of public transportation to many of the country’s popular sites (many of which can only be reached with off-road vehicles) all but precludes this option for travelers-on-the-cheap. Unless you take your own 4x4 vehicle into the country, which can be prohibitively expensive and involve substantial red tape with Libyan bureaucracy, the most viable option for visitors like Bobby and me is to join an adventure tour.

I stand before the ruins, which are spectacular. There is no other word. And I’m not the kind of person who usually gets into Roman ruins, can only handle about a day of them. But here at Leptis Magna—Latin for the Great Leptis—the city is so well-preserved that it allows you to dream. There are the marble-covered pools of the Hadriatic Baths, great Corinthian columns rising 30 feet. There is the nearly intact coliseum, three stories high, where you can crawl through lion chutes and explore the gladiators’ quarters. They don’t make cities like this anymore, every architectural detail attended to, no plan too lavish, no material too dear. Bearded gods gaze down from friezes. Maidens and warriors lounge among the carved porticos. Even the communal toilets remain nearly unscathed, the marble seats shined by thousands of ancient buttocks.

Libya is a land overflowing with antiquities. Beyond its extensive Roman and Greek ruins are some of the best ancient rock carvings in the world. Testament to when the Sahara was once verdant and life-supporting, many of Libya’s southern mountain ranges are dotted with petroglyphs, magical scenes which began to be created some 12,000 years ago: men hunting rhinoceroses and riding horse-drawn chariots.

It reminds me that so many empires have come and gone in Libya. The Garamantes, the Phoenicians, the Greeks. The Romans, Byzantines, and Arabs. And more recently, the Turks, Italians, and British. Even, for a few decades after WWII, the Americans, who operated an air base on Libyan soil. I walk to a Roman lighthouse rising over the Mediterranean, following a beach littered with building stones from Leptis. Waves caress the giant chunks of marble, slowly reducing them to the smooth white pebbles beneath my feet. There is too much of Leptis to save. It was too great, too vast. That it could end—I shudder at the thought. Theories abound about the cause of its demise. A great earthquake. A flood. The fall of the Romans and the later invasions of the Arabs. Slowly, perhaps imperceptibly, the sands took over. Will that be, I wonder, the fate of Qaddafi’s utopia?

*

Driving anywhere in Libya takes days. It’s larger than Alaska with one of the lowest person-per-square-mile ratios in the world. We cruise through the western desert, headed south, away from the mere 2 percent of arable land along the coast. The country appears as an empty wasteland of gravel plains and sand. Rarely does a bush break the monotony of sky and earth. Rarer still are trees. Or animals. On occasion I catch sight of a feral camel lumbering along the highway, but where it’s going is a mystery. Water is absent from the landscape altogether, appearing only in half-hearted spurts from gas station spigots. It is easy to understand why the majority of Libya’s population clings to the coast.

I travel with a guide, Magdy [pronounced Máj-dee], assigned to me by the Tripoli tour company. He is wary of me, knowing that I’m a writer. His friend recently took around a writer-photographer pair from England, discovering later that they worked for the BBC and had chosen Libya for their “Holidays in the Axis of Evil” TV series. When the couple got back to the U.K., they spun their innocuous Libyan tour into an exaggerated, terrifying journey into the heart of Islamic fundamentalism. The Libyan government protested; Magdy’s disillusioned friend resigned as a tour guide. And now Magdy, himself, guards what he says to me. It doesn’t help trying to explain to him that only the Brits could have come up with something as good as a “Holidays in the Axis of Evil” TV show.

“Where are these terrorist cells in Libya?” Magdy asks rhetorically as we drive along. “I’ve never seen them.” There is honesty in his voice. And frustration, too, to have his country negatively typecast by the West. But of course no one suspected such cells existed in the U.S., either, until September 11th, 2001. I stare out at the rocky brown plain, trailing off into heat waves. Are terrorist bogeymen out there somewhere, crouching in the dust, waiting to get their hands on me? According to the U.S. State Department: You could bet on it.

In the distance appears a flash of white-washed buildings and a flourish of date palms: Ghadamis. The ancient Berber caravan town sits among verdant oasis fields, once a major stop on the old caravan route from Timbuktu and still a way-station for weary Saharan travelers. The Berbers—North Africa’s indigenous people, who speak their own language and maintain unique culture traditions—make up an estimated 2 percent of Libya’s largely Arab population. Ghadamis remains their stronghold in the seas of sand, though it fell victim to Qaddafi’s modernization plan, the inhabitants forced out en masse in the 1980s into modern apartments in nearby New Town.

Some people, however, wouldn’t leave this charmed place without a fight, and it is easy to see why. Ghadamis is less a town than a gigantic labyrinth of narrow passageways that cut around and beneath adobe homes. Living here is like living in a subterranean world, the sun and its heat cut off by the rise of centuries-old buildings, each built into the next and accessed by an interlocking tunnel system. Now deserted, the town has an eerie quality of being just unearthed. Feeling like an archaeologist, I explore the dark, empty passageways with my flashlight, coming upon dead ends and mysterious chambers built from Roman columns. I squeeze through an open palm-wood door, climbing dusty stairs to the highest floor. Part of the ceiling has fallen in, incongruous sunlight gleaming on white walls painted with cryptic red Berber designs.

Maneuvering through crumbling piles of adobe bricks and debris, I reach the roof and gaze out on a scene out of Arabian Nights: countless white-washed terraces spreading toward the setting sun and the distant sand hills of Algeria. Nearby, palm gardens resound with birdsong and the burbling of aquifer water. The call to prayer wails from the squat mud minarets of a nearby adobe mosque, and I can only take it all in silently, reverentially, like a devotee.

*

I escape from the maze of streets into the dusk of Ghadamis’ New Town, the evening strikingly sedate. “Nightlife” requires a new definition in a country without alcohol, where the population abides by strict codes of male-female conduct that require both sexes to stay virgins until marriage—there are no dance clubs, no bars, no young couples strolling down the street, holding hands. And in conservative country towns like Ghadamis, the subdued air feels like perpetual Sunday morning. I go in search of the town hotspot and discover it to be the local internet café, where crowds of young men play video games, enter English-language chat rooms, and examine—however surreptitiously—Western porn sites. It takes me a few minutes to notice that there’s not a single woman in the place. Away from the progressive cities of Tripoli and Benghazi, women stay largely in the home, out of sight. A local man, Mahmud, tells me that women here aren’t allowed to see or interact with males outside of their immediate family, including any would-be husband.

I ask him how one goes about getting a wife then, given such circumstances.

“If you fancy a girl,” he says, “let us call her Fatima, you go to the father of Fatima and tell him that you want to marry his daughter.”

“But how,” I ask, “do you know if you ‘fancy’ a girl if you’ve never seen or talked to her before?”

“Well, yes,” he agrees, “this can be difficult.” But in his case he had met his wife when they played together as young children. As an adult, he recalled their youthful romps and asked for her hand in marriage.

Dowries are still an important part of Libyan culture, too, Magdy explains to me. Often, a potential groom is required to exhibit a large sum of money in cash to the father of the bride—perhaps a year’s wages or more—to prove his ability as a provider. Given this requirement, in addition to the grave cultural responsibility of wedlock, Magdy tells me that many Libyan men decide not to marry.

“So if you’re one of these men who never gets married,” I ask him, “does that mean that you never have sex in your life?”

Magdy has told me that I can ask him anything, but now he looks down, embarrassed, and tries to hold back a smile. “Yes,” he says finally. “It can mean this.”

Bobby, overhearing our conversation, blushes and rubs the back of his neck.

“Wow,” I say.

*

I finally cross paths with Clapperton in the town of Murzuq. He made frequent visits to the bey, or ruler, of Fezzan, who lived in a castle in town—an impressive stone structure that still stands, rising over a deserted courtyard that once held a booming slave market.

Historically, Murzuq sat midway on the caravan route between Tripoli and the sub-Saharan African kingdoms of Bornu, Wadai, and Darfur (modern-day Nigeria, Chad, and Sudan). Libya’s history is inexorably linked to the slave trade, as the country had few natural resources and depended almost exclusively on the sale of slaves for its survival. Between the seventh and 19th centuries, half of the estimated nine million to 14 million black Africans—mostly women and children—that crossed the Sahara to Arab coastal markets (numbers comparable to those sent across the Atlantic to the Americas) passed through Libya. Most would have entered Murzuq, where slaves were sold to middlemen or “fattened up” for further travel to Tripoli, Egypt, and beyond.

Slaves weren’t the only ones to cross this desert. In the early 20th century, explorers passed through this area in search of one of the world’s last great mysteries: the Lost Oasis of Zerzura. In the 1920s, when exploration was all the rave, rich young adventurers gathered under the auspices of the Royal Geographic Society of London to form the Zerzura Club, dedicated to finding the truth behind the legend. Originally mentioned in a 15th-century Arab text, The Book of Hidden Pearls, Zerzura was described as a “white city” in the midst of the Sahara, full of “great riches.” The first European reference to it appeared in 1835, in a book written by a British egyptologist; there was a reference to an oasis deep in the Libyan Desert full of palm trees, springs, and ancient ruins. Still, by the 20th century, no one had found it. If it existed at all, explorers surmised, it must be located in the middle of the nearly impenetrable sands of eastern Libya. Technology finally caught up with the search in 1933, with Hungarian Laszlo Almasy (the real-life English Patient) flying his biplane over three unknown wadis (dry river beds) hidden among cliffs. Further exploration on foot revealed no sign of gold or ruins, but Almasy was convinced that these were the Zerzura oasis. His discovery all but closed the books on the legend, though some scientists and explorers still believe it has yet to be found.

As I do. I conduct my own search for information about Zerzura among the supposed caretakers of the secret: the fierce, nomadic Tibu people, Saharan aborigines whom some experts believe to have inhabited Zerzura. Clapperton described them in his journal as “thieves to a man [who] steal from all.” The reputation still stands: the presence of armed, outlaw Tibus prevents me from traveling through various regions of the Fezzan in search of Zerzura.

It isn’t easy finding this elusive people. They number only about a thousand in Libya, and I hear about a small scattering of them on the outskirts of the desert oasis of Zawilah. As our Land Cruiser approaches the unusual clusters of conical thatch huts sitting on a dusty wasteland, I feel my apprehension rise, recalling explorers’ terrifying accounts of confrontations with the Tibu. But when I exit the vehicle, their chief, Sidi Loso Mohamed, greets me cordially and welcomes me to his village. Noticeably, no one speaks Arabic. Unveiled women come out to meet our group, unperturbed by the presence of male strangers. I ask some of the older men of the tribe if they know anything about the location of Zerzura. Their eyes dart over my face. They smile quickly, cryptically. No. They know nothing. Almasy allegedly tricked an old Tibu camel herder into revealing the names and locations of the Zerzura wadis, but these men will tell me nothing.

I give up the search for now and we head east to the village of Termissa, where the road and civilization—ends. We have a second vehicle, a truck: a safety precaution for deep Saharan travel. Our entourage now includes two drivers, Omar No.1 and Omar No.2, a cook named Mohamed, and Magdy, making six of us in total. We’re in search of a spectacular desert anomaly that rises from the center of the Sahara: an extinct volcano called Waw an Namus, Volcano of the Mosquitoes. Finding it will require several days of off-road driving through one of the driest deserts on earth, lucky to receive a millimeter of rain every three years. We’re bringing several large jugs of water, as well as an entire petrol drum of fuel, just to be on the safe side.

We enter the western edge of the Libyan Desert, crossing a flat, roadless plain of sand. Omar No.2 hits the gas, but no matter how fast we move, no matter which direction we look, the view remains exactly the same: flawless blue sky stretching over amber-colored sand. The Land Cruiser’s odometer reads 60—70—80 miles an hour. Nothing changes. We shoot through an empty, vast landscape that makes a mockery of speed, that seems to have no beginning or end.

Our Land Cruiser slows down as we descend from a high plateau onto a gravelly plain that runs between two mountain ranges. It’s getting hot: My thermometer reaches the high 80s and keeps climbing. There is no sign of life—no trees, no bushes, no animals. Just the rocky expanse of the Libyan Desert. Up until the beginning of WWI, this desert remained one of the world’s last unexplored regions; to attempt to cross it was suicide.

As the sun sets, we stop to set up camp below a high white dune, and I lay my sleeping bag under the stars. Sleep in the Sahara and you can see every star in the graceful curve of Orion’s bow, the great sweep of the Milky Way at his back. A small desert rat climbs over me and stops only inches from my face, looking at me. No fear. It has never seen the likes of me before, probably never will again. I move a hand toward it, and it takes a brief step forward before slipping off into the night.

I discover that the desert has its own soul. And it isn’t insignificance that I feel in the face of this, but the aching candor of being alive. These great dunes around me—carved and shaped by the wind, baked by the sun—were once stone. And if mountains can dissolve, then what of me—so much more fragile, so much softer, so quick to bleed and easy to destroy. Maybe it’s heady reflection, but I think it, lying in the sand and gazing at this world: the marvel that I am here. The marvel of it. And that is all I seem able to put into words. That I can endure out here, in my sleeping bag, under stars too innumerable to calculate. Such an ecstasy of wonder and gratitude. I am here, I am here!

*

The volcano, Waw an Namus, reminds me why I travel: to see what cannot be imagined, to be taken into my dreams. It rises from the gravel plains of central Libya, a large black mountain several thousand feet high, 20 miles round. We drive to the top. Though the volcano was officially discovered by an Italian explorer in 1931, the nomadic tribes of the Sahara have known about it for centuries; according to local legend, they sent offenders here to be exiled.

But what a place to spend the last days of one’s life, looking down into the crater, from the lip of the enormous volcano, at a turquoise lake surrounded by palm trees. Seeing any water at all in this desert—let alone a large lake and a verdant spread of grasses—is more than I could have asked for. It’s surreal. Unbelievable.

I hike down to the bottom of the crater with Bobby, while Magdy and the others take the vehicles. What looked like grass from the top of the volcano are, I see, thick patches of reeds that surround the lake. Hoping to reach the water, I shove my way through them. They only part with a fight, and I look down to see blood covering my hand: a reed has cut through the meaty underside of my finger to the bone.

Still, I’m too close to the water to give up now. Pushing through one last patch, I emerge on the edge of the lake, which proves to be so large and deep that the wind cuts waves across its surface. Salt and mineral excretions have solidified along the edge of the pool, over thick black mud. As I walk to the water, I sink to my thighs in the muck, my clothes and hiking boots saturated with the foul smelling ooze.

Magdy and the others look at me, alarmed, as I emerge from the thicket, clothes saturated with mud, hand covered with blood. My finger needs stitches, but as we’re 250 miles from the nearest civilization I ask Bobby if I can borrow his sewing kit. He has one of those cheap jobbies they give away in hotel rooms, with a fat, dull needle wholly inappropriate for piercing tough human skin, but I thread the needle and do my best. The blood makes things slippery and inconvenient. Magdy and the Omars stand back by the car, watching in horror. I finish up, cutting the excess thread with a pair of toenail clippers. Just like working with leather back home.

*

For the past few days, we’ve been busy following Clapperton’s trail to the far southwestern corner of the Fezzan. This region, known for its mountains, the Jibal Akakus, attracts more tourists than any other area in Libya. With giant stone arches, narrow mesas, and otherworldly rock formations, the Akakus are a geologist’s paradise, offering, indisputably, some of the most unique desert vistas in the world. Bobby, an accomplished climber enamored of the small black sandstone spires, has been practicing his bouldering skills while I wander among the rocks, listening to the desert’s silence.

But just as Clapperton went on to the old Saharan caravan town of Ghat, so do we, arriving just after noon in a dusty, idyllic town of around 16,000 people. Once a major stop on the trading route from Timbuktu, Ghat was—and still is—controlled by Tuareg tribesmen. This hearty nomadic people can be found all over the Sahara, though in Libya most have settled down in towns.

We rendezvous with the Tuareg man who is supposed to guide us for the next few days. But after Magdy explains our plans, he says, “To hell with you,” and walks off. This becomes the usual reaction whenever we approach any Tuareg about guiding us, and all because I want to visit to the “Devil’s Hill.” Kaff Jinoon. It’s a curious series of eroded sandstone peaks jutting from the dunes north of Ghat. Unique not only for its two obelisk-like spires, or horns, it’s also believed to be Grand Central Station for genies—spirits—from thousands of miles around. And not just any spirits, but those most wicked and base. The spirits of torturers and murderers. The spirits of those wrongly slain. Lost and sickened souls, attracted to the vortex that is Kaff Jinoon.

*

Clapperton and his companion Dr. Walter Oudney camped near the mountain, to the terror and vexation of their Tuareg guides who believed that small, red-bearded devils lived on it and caused mischief to all who passed, while spirits taking on the appearance old men materialized out of the night to terrify lone travelers. It was considered akin to suicide to go anywhere near the dreaded mountain. Wrote Clapperton, “[My guide] Hatita said he would not go up it for all the dollars in the world.” And it’s the same story now in Ghat, no Tuareg willing to travel with us to the mountain, no matter how much we’ll pay. They all have their own stories. There were the French tourists a few years back. They drove out to the mountain, thinking it’d be a good joke to climb it, but as soon as they got out of their car they were attacked by swarms of wasps. Libyan authorities found the group wandering along the road, unable to get in their vehicle, their faces covered with stings. And this, I’m told, was minor. Much worse has occurred. Like the Libyan soldier at a checkpoint near the mountain who saw something so awful, so terrifying, that he went into shock and couldn’t walk for a year. To this day, he is unable to speak of what he saw. And then there is the man who swore by Allah that he saw an entire army division march around the base of the mountain one night—a ghost army, that disappeared before his very eyes.

Jinoon and its vicinity has been considered a stomping ground for evil genies for centuries. Intrepid Arab traveler Ibn Battuta first wrote about this desert in the 14th century, describing it as a place “haunted by demons; if the [traveler] be alone, they make sport of him and disorder his mind, so that he loses his way and perishes.” Western explorers journeying in the Fezzan regarded such tales with derision, determined to see the mountain and to try to climb it. In 1822, Dr. Oudney made the first recorded attempt, reaching the mountain’s 4,500-foot-high saddle and returning without incident. “The Doctor has got a high reputation for courage for his visit to Jinoon,” Clapperton wrote about his friend’s successful climb, “and every newcomer is sure to ask him about it.” Later explorers were less successful. British adventurer John Richardson attempted the climb in 1853, getting lost on the descent and wandering in the desert, near-death, for two days. Robust German explorer Heinrich Barth had an almost identical experience in 1857. I am determined to see the place. I want to climb the mountain. we decide to go there unguided.

Magdy tells me that Omar No.2 pulled him aside last night to ask if I’m crazy. Don’t I know that it’s lunacy to climb Jinoon? If Magdy were a truly responsible guide, he would advise me against it before something awful happens. But Magdy shrugged. He is a cosmopolitan with a degree in French Literature. He lives as far from this corner of the Fezzan as a person in Anchorage lives from Tucson. What does he know? If I want to risk my life climbing a mountain haunted by demons, so be it. Insha’allah, God willing, I’ll make it to the top and back down again.

Bobby is the least chagrined of the group. He recently lost one of his closest friends in a car accident. So screw the evil genies. Hell, maybe something good will happen to him if he climbs the mountain.

We strap on our backpacks and head up the nearest slope. The ground is covered with rocks and boulders that prevent any kind of easy walking. Still, gratefully: no wasps. We ascend a ridge on the far western edge of the saddle—some distance from the mesa, but seeming to provide the smoothest way up. In a short time, we reach the top. Golden dunes spread out like serpent trails across the valley below. Beyond them, the black rise of the Idihan Murzuq massif glitters in the heat waves. I see that I’m standing on the broken remains of fossilized plants—a whole mountaintop of them, as if Medusa cast her eye upon a prehistoric jungle, turning it to stone. I find a piece of an old climber’s rope lying among the rocks. dr. Oudney’s? The hemp crumbles to dust in my fingers.

This has been the easy part. We hike along the top of the saddle, the route barely three feet across with sheer drops on either side. It’s more like a bridge, the wind fierce and slapping my hair across my face. When we reach the mesa, it doesn’t look good: A great wall of stone rises 40 feet before us. After scouting around, we find a fissure of loose sandstone. It is our only way up and, thankfully, Bobby goes first. I watch him climb slowly, meticulously, pieces of rock breaking off beneath his feet. Footholds and handholds are few, but he welcomes the challenge. I don’t, following reluctantly. This would be the time for some mischievous genie to push me to my death.

Nearly to the top, the rock I’m standing on loosens and snaps off, shattering on the boulders below. I cling desperately to the cliff, searching for a new place to put my feet, finding only an unreliable ledge. Shaking from adrenaline, I keep climbing, finally reaching the flat top of the mesa where I realize a climber’s greatest anxiety: getting back down.

But it was worth it. Before us is one of the two spires—a giant rectangular block of sandstone rising over 120 feet, with flat sides and sharp 90-degree angles, its proportions so near-perfect that it almost looks manmade. It has such an uncanny resemblance to an obelisk that I search its sides for signs of ancient writings. Nothing. There is no sign of humanity whatsoever on this small mesa—no cairns, no climber detritus, no markers. Other climbers must have made it up here, though I can’t be sure.

Down below, a tiny dot of white in a sea of sand, sits the Land Cruiser, waiting for us. Bobby and I enjoy the view for a while, but I’m anxious to get back down, to get off this mountain. Genies may not have attacked me, but I do feel as if I’ve pushed my luck.

We descend the same way we came up, looking for our own little cairns to show us the route down the rock faces. Before long I’m on the rocky slope below the saddle, heading in the direction of the vehicle. It occurs to me that Libya, itself, is like Jinoon. The den of the evil genies. The bastion of all my fears. Al Qaeda. Terrorist cells. Qaddafi. A country full of bogeymen lurking in every crevasse.

When Magdy and the others see me and Bobby safely returned, they smile and let up a cheer. So much for all our fears.

*

We stop at a tourist camp along the highway outside the town of Oubari and indulge in our first shower in nearly two weeks. And a hot shower, no less. Omar No.1 is literally singing in cleanliness as we both hang our laundry on acacias to dry in the sun. Happily, I can get a comb through my hair again.

Gloriously refreshed, we head off to Gebraoun Lake. One of the largest salt lakes in the Sahara, it’s a great place to sunbathe and swim. I change into a pair of shorts and a tank top—risqué to the Omars, who give me a double-take—and jump into the lake, watching Bobby clamber up a 1,000-foot-high dune: Gebraoun is the only place in Libya where you can sand ski. He reaches the top, puts on the skis he’s rented, and a moment later he’s shooting downhill, kicking up clouds of sand.

I’m still hoping to find Clapperton among these eroding sand and rock plains of the Fezzan, to pick up his exact trail. I arrange to hire camels and Tuareg guides so that Bobby, Magdy, and I can re-create one of his most treacherous desert journeys—his route deep into the Oubari Sand Sea to a remote oasis called Trona.

We arrive at the town of Terkiteba to rendezvous with our Tuareg guides, Salaka and Mohamed. They have five camels with them, including a pure white maherry. This latter, an expensive pedigree animal descended from Arabian racing lines, carries its dainty head higher than the others, whiffing gracefully at our scents. The other four are a motley group of mutt camels from Chad: a black, belligerent one that roars and froths at anyone who comes near; a sprightly gray one with white splotches; and two beige ones.

The Tuaregs choose two as pack animals and load all our gear and supplies into bags on either side of their bellies, the unlucky pair growling in wrath with every tug of the girth. The ultimate desert machines, camels can drink nearly 25 gallons at one fill—more than twice what it takes to top off the tank of my Toyota back home—lasting them, in the cooler winter season, several weeks without a refill.

Clapperton tried to take a maherry camel back to England with him as a gift for the King of England, so I ask if I can ride ours to see what the big deal is. The Tuaregs tug at its nose reins and hiss the animal down to a bony-kneed squat. I use the curve of its neck as a launching pad, leaping into the saddle, and it raises so abruptly that I’m nearly thrown off. These Tuareg saddles must take a lifetime to get used to: the seat is small and hard like the top of a stool, with a narrow piece of wood in front and back meant to secure the rider in place (in theory). For some reason, the front saddle horn has three sharp points, the only purpose of which seems to be to impale camel, rider, or both should you fall. I nearly miss being skewered several times as my sleek white maherry decides, on a whim, to sit down. And it doesn’t just sit, it falls, a kind of headlong lurch that sends me tumbling to the ground.

The Tuaregs decide to try me on another, the largest of their camels, an enormous beige creature called Watani, meaning “The Patriot.” Sitting on top of him, my toes barely touch his neck. The only one of our five male camels that was allowed to keep his testicles, he walks with a slow, proud strut as we head off into the desert. Camels themselves are more a novelty than a necessity in Libya these days, with the formerly nomadic peoples buying cars and settling down in Qaddafi’s modern towns so their children can receive an education. Libyan Tuaregs still keep some camels in the family for wedding ceremonies and racing, but most of the Tuaregs I’ve spoken with agree that the nomadic life of Libya is all but gone.

Which might explain why, as we head across the desert, we become a tourist attraction, flocks of Land Cruisers making a beeline toward us. These frequent visits scare the camels and halt our pace, as guffawing French and Italians line up to get their pictures taken beside our Tuareg guides. But soon, thankfully, we head north into deeper desert, the Land Cruiser trails vanishing from the sands. We travel through a gradually rising valley, encircled by high beige dunes, our barefoot Tuareg guides leading their camels. It becomes only us and the sun now, which burns my skin even as a cool breeze gives me constant gooseflesh. There is no getting comfortable in the Sahara—it is always too hot or too cold, as if out of spite.

At sunset we stop among the dunes to camp, the peace of the desert like a blanket over us, calming thoughts, settling moods. The scene seems almost perfect—

Then we get the news. Someone forgot to pack our drinking water.

“Un-freaking-believable,” I say to no one in particular. What would Clapperton think?

Magdy searches through our baggage strewn about the desert. All at once, he makes a discovery: the dishwater! He’s found a jug of it.

“And it’s safe to drink that?” I ask, incredulous.

“No problem,” he says.

But early the next morning, my bowels do a double-take. I might actually have a bowling ball caught in my intestines. Our Tuareg guides seem unfazed, getting up after dawn, eating a slow breakfast, and taking all of three hours to load the camels and break camp. We leave at the pitiably late hour of 10a.m., whereas Clapperton and his guides left each day at around 5a.m., typically traveling 12 to 15 hours a day. “[We] travel from before sunrise to sunset without halting,” Clapperton wrote, “having only two meals a day—one before we start and the other after we halt for the night.” We, on the other hand, end our second day well before sunset, stopping near the small salt lake of Umm al-Maa.

I hold a powwow with everyone, Magdy translating, and ask our two Tuareg guides if we can’t try to do things the way Clapperton did. No being easy on us foreigners. No late breakfasts or early dinners. I want to experience real-deal camel travel, from dawn to dusk.

Reluctantly, they agree. As I go off to take a swim in Umm al-Maa, I’m beginning to fear what I’ve asked for.

*

The next morning, everyone is up early and mobilizing, breaking camp and packing animals. And we have a new guest, a Tuareg named Yahya, whom Magdy brought in to guide the two Tuaregs who are supposed to be guiding us. Wearing a traditional Tuareg face wrap and a not-so traditional fluorescent yellow jacket, Yahya proves to be the real-deal—he doesn’t tolerate loitering, frequent stopping, bathroom breaks, or anything that can result in a slowing or stopping of our pace. Already, I like him immensely. A go-go-go kind of guy, he takes hold of the reins of the majerry and begins walking, never looking back. If we want to get to Trona tonight, he insists, we will need to get moving—and stay moving—for the entire day. Expect at least 11 hours of travel.

Our less-than-the-real-deal Tuareg guides yell out, begging him to stop and wait for us, but he’s having none of it. We all scamper to get organized and mounted on our camels. Just as I’m about to leap onto The Patriot, I put a hand where I shouldn’t on his neck, and he swings his enormous head over like a crane, chomping down on my calf. Still, there are things to be grateful for—for instance, that camel teeth aren’t exactly pointy, or that, by luck, I chose to wear my long johns beneath my pants, protecting me from what could have been two very deep puncture wounds. But camel jaws are still similar to a pair of vice grips, easily squashing muscle, and in a short while my lower leg begins to turn black-and-blue.

Meanwhile, Yahya is a tiny figure in the distant heat waves, his fluorescent yellow jacket like a beacon in the great sea of sand. No longer on speaking terms with The Patriot, I trade him in for the friendly gray camel, which is refreshingly low-maintenance. Basically, all I have to do is steer and hang on. Our group rushes to catch up with Yahya, and we leave behind a wide valley, heading into high dunes. It’s fortunate for us that he knows where he’s going, because none of the rest of us do. One dune looks just like another; it would be easy to get lost among them. Yahya tells us about finding one such unfortunate a few years ago—reduced to a dried-up corpse in the sand. Never underestimate the desert.

As the sun begins to set, we follow a narrow wadi due east. Finally, there are bushes and signs of life, a large-eared fox trotting behind a dune. Yahya has been walking at a near-jog, barefoot, for over nine hours now, stopping only when the rest of us decided to have lunch. And he hasn’t once drunk water or taken a toilet break. Little wonder that the Tuaregs still carry a reputation for endurance and hardiness in the desert. Me, I try to walk along with him, leading my camel, but the coarse desert sand soon scours the soles of my feet and covers them with blisters. The trade-off is riding, but the saddle chafes my inner thighs and ass until they feel raw. How, I wonder, can anyone travel like this for more than a few days? Yet, Clapperton did it for months. For years. I imagine the weeks he must have suffered until he became habituated to the saddle. I wonder if there’s anyone left in this world who compares to the explorers of old.

The bad water I drank the previous night has me bloated and nauseous, the jouncing of the camel only exacerbating my discomfort. I want to get to Trona—and soon. Already, the sun has set. Our group climbs up the steepest dunes we’ve yet encountered and, at the top of the highest, we look off into the dusky distance. Down below is an enchanting site: an island of green that can only be Trona. Nestled in the nook of sand hills that rise several hundred feet, the uninhabited oasis, with its quaint blue lake and forests of date palms, looks all the more wonderful after nearly 12 hours of hard travel. The camels raise their heads and sniff the air. Yahya begins to sing. Everyone—human and beast—suddenly picks up speed, rushing down the dune and trotting anxiously to the sanctuary of green. “We arrived in Wadi Trona,” Clapperton wrote, “and pitched our tents amongst the date trees. Hadje Ali brought us some water—which we drank with a greater relish than if it had been the sweetest wine.”

In Trona, there is still freshwater, a cool oasis pool, and all the dates I can eat. But, more important, there is rest.

*

Though I’m back in Tripoli, I’m still at Trona in my mind, sitting in the silent emptiness of the Sahara with the stars above whispering their infinity. Walking with Magdy along the noisy streets of Libya’s capital, I come upon a zawia, a Sufi mosque, which is having its evening service. Sufism is considered heretical by many Muslims for its belief that one can merge with God—a belief that has forced this mystical tradition underground in many Muslim countries. In Libya, however, it enjoys a place of tolerance in society, a zawia found in every major town across the country.

Chanting filters into the dusk, and I ask Magdy if I can witness their ceremony. We enter the zawia’s long courtyard. The sheikh comes out—the equivalent of a priest. Magdy explains my interest, and Sheikh Hamza tells me that I can watch the ceremony through an open window, but it’s the best he can do: Females are not allowed inside. I take my place where instructed, looking through metal bars into the prayer hall.

The ceremony, or dhikr, begins. Men form two large circles, some of them glancing at me through the window with suspicious, questioning eyes. A man begins playing a guitar, singing the poetry of Muslim saints, and the group starts beating on little drums. All of this is unique to Sufism, Magdy explains; it is how initiates meet God and enter into union with Him. The two circles begin swaying and bobbing, slowly at first and then more frenetically, my own body moving to the rhythm. The music increases in volume. “All-ah, All-ah,” the men chant, louder and louder, their entreaties turning into shouts.

After close to a half hour of this, the music reaches its peak, becomes a great cacophony of sound that stops with such abruptness that the ensuing silence seems almost profane. Everyone looks around, as if returned suddenly to earth, unsure momentarily of where they are or why. And now something strange is happening throughout the room—bodies contort, limbs freeze into strange positions; men drop to their knees, quaking and sobbing. Those who can move help the ones who cannot, massaging bodies back into movement and holding anyone who cries. One man points helplessly to his throat, as if something were stuck inside. Water is brought and poured for him, which he swallows in a rush.

The ceremony over, an assistant passes around little shot-glasses full of coffee with slices of bread. I don’t expect him to remember about me, but he comes over to the window, smiling, offering me a glass. As the men file out, I stay back, away from the courtyard, but no one seems to mind my female presence now. When I see the man who’d been clutching his throat, I call out to ask him how he is.

“Kway-yis,” he says. Good. His eyes are bright and dancing. “Where are you from?”

It is my last night in Libya, and yet the question still gives me a touch of fear. “America,” I say.

He looks unfazed. “Have you seen a Sufi ceremony before?” he asks.

I tell him no.

“You are welcome,” he says.

|

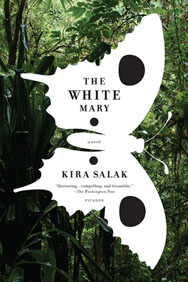

THE WHITE MARY

by Kira Salak

"A gripping debut novel."

Publishers Weekly Pick-of-the-Week

"There aren't many books that we hand to friends, urging,

'You have to read this.' The White Mary is one of them."

Cleveland Plain Dealer

"Riveting."

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

"With The White Mary, journalist Kira Salak makes a stunning

debut as a novelist. This is a story whose beauty and power

sweeps you along, like the jungle rivers that bear her heroine

into the heart of New Guinea in search of a vanished American."

--Philip Caputo

|

© 2008 Kira Salak, KiraSalak.com--all rights of reproduction in any form reserved

![]()